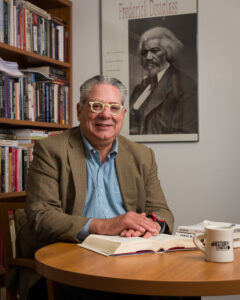

Paul Finkelman, President of Gratz College, a distinguished visitor to Gustavus, and the leading historian of slavery and the law, talks about the proslavery U.S. Constitution, Chief Justice John Marshall’s buying and selling of enslaved people, the proslavery jurisprudence of the antebellum Supreme Court, and the present-day monuments conflict.

Season 4, Episode 2: “A Covenant with Death”

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus is produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of Gustavus Office of Marketing. Will Clark, senior communications studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast, and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

In 1854, the abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison publicly burned a copy of the US Constitution calling it a pro-slavery covenant with death and an agreement with hell. Garrison would be grateful for my guest today, historian Paul Finkelman. No one knows more about the pro-slavery history of the Constitution and the pro-slavery jurisprudence that flowed from it.

Three summers ago, I had the pleasure and privilege of studying some of that history in a National Endowment to the Humanities Summer Institute on the topic in Washington, DC, which Professor Finkelman co-directed with humanities educator Paul Benson. A distinguished legal historian, and currently president of Gratz College outside Philadelphia, Paul has authored and edited a staggering number of books, articles, and essays in legal history, especially concerning slavery and the law. His most recent book, Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s Highest Court was published by Harvard University Press in 2018. He has been cited five times by the US Supreme Court, most recently in a 2019 majority opinion by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

In addition to his vast and influential scholarship, as well as his frequent speaking engagements, Paul has held numerous distinguished teaching appointments at such institutions at the Albany Law School, the University of Tulsa College of Law, Duke University, and the University of Saskatchewan College of Law, to name just some. He’s also been awarded numerous fellowships, for example, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Philosophical Society, the Library of Congress, Yale and Harvard University in the American Council of Learned Societies. I’m proud to say that he’s also been to Gustavus twice as a distinguished guest lecturer in 2019, sponsored by the Hanson-Peterson Chair of Liberal Studies and as a guest professor in two of my courses this past March. I’m delighted we have this opportunity to converse yet again. Paul, welcome to the podcast, which we will count as your third Gustavus visit.

Paul Finkelman:

Well, it’s a pleasure to be there. I’m sorry that we can’t enjoy the greater Twin Cities in person, but this will have to do.

Greg Kaster:

I agree it would be fun and we were just chatting before we started recording the last time you were at Gustavus was literally the day before our respective institutions shut down due to the pandemic but yeah at least we can do this remotely. So thanks so much. Let’s begin. We’re both historians so we are interested in people’s history, of course, histories. How did you become a historian? When did you know that is what you wanted to do, wanted to be?

Paul Finkelman:

That’s a complicated question. I went to school in the… I entered college in the late 60s at a time when there was great ferment at universities about civil rights, about the Vietnam War, about the beginnings of the environmental movement. I was interested in social protests since I was involved in many marches and demonstrations. I inhaled my share of tear gas and at the same time I became interested in why do some social movements work and others don’t work and so I studied past social change as an undergraduate and I looked at Socialist Party and the Communist Party and various others similar events, and I thought that in many respects, they were both not about America. That is, I think the Communist Party was singularly unAmerican, not in the way the House Committee on American activities did it, thought about it that is, but simply that it never understood what America was all about.

I felt that the struggles of labor unions were important for American history, but they were always about what the workers wanted for themselves. And then I began to study the anti slavery movement. And what struck me about anti slavery is that it was for the most part, a movement populated by people who had never been slaves, who were for the most part white, and they were concerned about slavery because it was morally unjust. They were concerned about an institution that was a cancer on American society. And it struck me that abolitionists were people who were worth knowing more about. So I began to study abolitionists and that led me to the study of slavery and I concluded while I was in college, that slavery was really at the center of American life, and had been not merely an institution that died out in 1865, but lives on and segregation lives on and racial attitudes and it lives on in our Constitution. So that led me ultimately to go to graduate school. To become a historian, I wrote a dissertation on slavery in the law and I have since written a lot and lectured a lot and thought a lot about the problems of slavery in American culture.

I’ve written about many other things as well, because, history is, as some people put it a seamless web, you go from one event, one subject, one problem to another, and the more you study it, the more you realize how little you know. So I’ve written about race discrimination against Asian Americans. I’ve written about discrimination against American Jews. I’ve written about the civil rights movement and I continue to be interested in what makes America what it is. That is the ultimate great contradiction between a society which says, “We hold truths to be self evident, and we’re all created equal,” and a society which countenanced segregation, discrimination long after slavery is over and so that’s been my trajectory. And on the side, I’ve done other things, I’ve written on baseball in law, for example, because although I’m trained as a historian, I ended up teaching in law schools for a variety of reasons. So I’m interested in how law affects society. I think things like slavery and race are the ultimate tests of who we are as a people.

Greg Kaster:

I agree and to back up just a little bit, you did your PhD at the University of Chicago, where if I’m remembering correctly, you worked with the legendary historian John Hope Franklin, is that right?

Paul Finkelman:

I did. I worked with John Hope Franklin, who was I would say the most prominent African American scholar of the last half of the 20th century and whose book From Slavery to Freedom, which is still in print after its first being published in 1947, really set the stage for the study of African American History and I also worked with Stanley Katz, who was a historian teaching in the law school, and is one of the great legal historians in the United States and is now at Princeton, went on to be at the Woodrow history department in the Woodrow Wilson School. So I had the advantage of having two incredibly important mentors who are really in quite different fields. But Chicago was a place where you work with lots of other people as well. So I took courses in geography, I worked with political scientists, I took courses with them and I took a lot of classes in the law school.

Greg Kaster:

And when did you start to focus on the Constitution itself in its pro slavery dimensions?

Paul Finkelman:

Well, my dissertation was a study of what happened when southerners brought their slaves into northern states. Now, I don’t want to get too involved in technical law, but basically, the issue would be this, if slavery is created by the local law or the local state, does the person remain a slave if you bring the person to a place where slavery no longer exists? Or does the slave become free? I suppose you could think about it in terms of modern property law because of course, under the legal system, slaves were property and here might be an example, I’m hesitant to use this example too much because it kind of diminishes the importance of the human element of slavery that is, these were human beings who were treated this way.

But let’s suppose you buy some marijuana in one of the many states where marijuana is now legal and then you travel to a state where marijuana is not legal. Obviously, the marijuana that’s with you will be taken away from you, confiscated because you can’t have it in this state, even though it’s legal in the state that you came from. Now, in a sense what happened with slaves is, they might be brought to free states and as a result of coming to a free state, they would in fact themselves become free under the state law. So this is the kind of issue that I studied to write my dissertation. There were many, many cases on this because many southerners traveled into northern states with their slaves.

These cases ended up in courts. They ended up with legislation being passed and so in that sense, from my dissertation on I was at least thinking about the Constitution and thinking about the way in which the Constitution operates and in order to do this, of course, I look at the debates on the Constitutional Convention and read the debates and read about the way in which they reshape the writing of the Constitution. Sometime after that, in 1986 after I’d been out of graduate school for a decade, I was asked to write an essay on slavery at the Constitutional Convention for a book called, Beyond Confederation, which was a collection of essays, book chapters, about the creation of the US Constitution and so I wrote an article which I called Making a covenant with death, which is why Garrison would like me, in which I wrote about how the constitution essentially made a series… contained many, many compromises over slavery, all of which protected slavery and embedded slavery and prostitution.

And since then I’ve just kept writing on this subject, written about Supreme Court justices, written about Supreme Court cases, written about state laws, written about political issues, written about the fugitive slave law. I ended up writing a biography of Millard Fillmore, who was the president to sign the Fugitive Slave Law, back in 1850 into law. So I just keep writing about this, because it’s endlessly interesting and more than that, I think it’s endlessly important for understanding who we are as Americans, what our country is all about.

Greg Kaster:

I want to come back to that latter point in a bit why it’s important, but first, let’s stipulate that the issue you were studying in graduate school was really the one that nagged at and ultimately tore apart the union [inaudible 00:14:00] enslaved people come into a free state, are they still slaves, but also that the Constitution is tough, our Constitution is peculiar, right? It never mentions the word slave or slavery or enslavement or those words, and yet there is a fugitive slave clause built into it and there’s some other ways, of course many ways as you’ve studied and pointed out, in which the Constitution is a pro slavery document, maybe you could tell us a little bit more about some of those ways.

Paul Finkelman:

Sure.

Greg Kaster:

Most Americans don’t really understand the extent to which the constitution was absolutely saturated with slavery without mentioning it by name. Right.

Paul Finkelman:

So when the Convention debates what’s going to go into the Constitution, the delegates talk about Negros and they talk about slaves, and they use the term interchangeably, which is interesting because of course by this time there are a fair number of free blacks living in the north and there are a few free blacks living in the south. So all black people are not slaves but the Convention delegates use the term negro and slave interchangeably and they talk about slavery in a variety of ways and southerners insist on counting slaves for purposes of representation. You remember in the Articles of Confederation which the constitution will replace, representation is based on state, each state has the same number of representatives, but the new constitution representation will be based on population and so the question is, “Do you count slaves as part of the population?” Curiously, and again, it’s also very complicated because it’s all interwoven. But let me back up for a couple years.

During the revolution under the Articles of Confederation, the states were expected to contribute money to support the national government, which meant to support George Washington’s army in the field and the states were expected to make contributions based on the population of each state. And the southern states insisted that you could not count slaves for purposes of making contributions because as they said, “Slaves are not persons under the law, they are property and what we’re doing is basing taxation based on people and slaves in this context are not people.” Now they’re not saying that slaves aren’t really human beings they know better than that and they’re certainly not… But what they’re saying is in a political context, in an economic context, slaves are not persons, they’re property. And so in the end, Virginia’s contribution or North Carolina’s contribution to support a new government was based entirely on its free population.

Fine. Now comes the Constitutional Convention and you’re going to base representation on the number of people in the state and suddenly the southerners say, “Well, of course slaves are people, and we have to count them for purposes of representation.” They’re completely dishonest, disingenuous, lying hypocritical, because for years, they have been saying that slaves aren’t people within a political context and therefore they shouldn’t be counted for taxation and now they turn around and say, “You absolutely have to count our slaves for purposes of representation.”

In the end, everybody agrees to a compromise known as, the three fifths compromise, which says that you’ll count slaves on the basis of three fifths of the population. So if you have 1000 slaves, it’ll only count to 600 people for purposes of representation. Okay, so in Article one of the Constitution, you get the three fifths clause. Now, it doesn’t say we’re going to count the three fifths of the slaves. What the clause says is, and I’ll read it to you, it says, “Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several states according to their respective numbers which shall be determined by adding to the whole number of free persons, including those bound to service for a term of years who should be an apprentice or an indentured servant, who are of course white, and ultimately free. So adding to the whole number of free persons, three fifths of all other persons,” I just cut out a couple of words here, I don’t want to read too much. But basically, the slaves are the three fifths of all other persons, but they don’t say the slaves, because they don’t want the American public to be aware of just how pro slavery all this is. So they hide the word because by saying the word, you’re going to expose the Constitution and its many pro slavery provisions.

Similarly, there’s a clause which allows the African slave trade to continue till at least 1808. Now this is important to understand. The new Constitution gives Congress the power to regulate international trade. Under this power, Congress could end the African slave trade because it’s international trade. Everybody understands that. But the delegates from South Carolina, Georgia and North Carolina say, “Look, we have to be able to import more slaves and we know that the Congress might vote to ban the African slave trade, so we insist that there be a protection against that.” And so how did they do it? With the following clause, “The migration or importation of such persons, as any of the states now existing, shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the year 1808.” They don’t say the slave trade can be rebutted. They call it the migration or importation of such persons, again, trying to hide what they’re doing. The [crosstalk 00:21:08] slave clause says the same thing, “Persons owing service or labor,” [crosstalk 00:21:12].

Greg Kaster:

Nor does that slave trade clause say anything about an internal slave trade, right? I mean nothing there.

Paul Finkelman:

Well, the internal slave trade is not there because nobody expects Congress to regulate the internal slave trade. We’re talking about the external slave trade, the importation from other countries.

Greg Kaster:

What about the Electoral College, which I was taught long ago was really about stemming a populist impulse, a democratic impulse. But you’ve argued that in fact, that’s not really the case, that really we can understand the Electoral College, which we still have of course, which has decided elections including presidential elections in 2016. We can understand that apart from its pro slavery functions or implications, could you say a little bit about that?

Paul Finkelman:

Sure. So, when they’re deciding how they’re going to choose the President, James Madison says in the debates that the most appropriate thing would be for the people to elect the president and then he says, “But we can’t do this because our Negroes, that is our slaves would have no influence in the election of the President because obviously, the slaves don’t vote.” Remember, you’re counting slaves for representation, you’re not saying that slaves can vote. Okay. So Madison and a couple of the other delegates come up with this clever idea that we will have presidential electives, which will essentially represent the slaves… the states, I’m sorry, represent the states and the presidential electors will be allocated by the number of representatives that each state has in Congress plus their two senators.

And in doing this, of course, the presidential electors are going to be based in part on the three fifths clause. So yes, the southern states get extra presidential electors because of counting slaves for purposes of representation and that gets Thomas Jefferson elected President in 1800. Without the Electoral College, Adams would have been reelected.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s exactly where I was going to head, the election of 1800. What did the Federalist call him? The Negro president or something referring not only to the-

Paul Finkelman:

Yeah. So one person wrote a book about Jefferson, and they called him the Negro president, because he was effectively elected by votes from electoral votes created by counting slaves.

Greg Kaster:

Well, we still have that Electoral College [crosstalk 00:24:35].

Paul Finkelman:

We do and it comes back to haunt us in every election and we’ve had a number of elections, not just 2016, in which the person who won the most votes did not get elected president.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, and it’s a direct legacy of slavery.

Paul Finkelman:

It’s a direct legacy of slavery, and nobody wants to talk about this, because if you talk about this then the electoral college is an embarrassment.

Greg Kaster:

Yes. All right. And then it presumably goes away or it may go away more easily.

Paul Finkelman:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Now what about this argument? I think it is Gary Nash’s book on blacks in the revolution, but the others have made it to that… Look, the founders, the so called founders of the Constitutional Convention affiliate, they really had no choice, those who didn’t want to compromise or maybe rather not have compromised with southern delegates really had no choice but South Carolina is going to walk out of the convention, right, Georgia… Maybe it was theoretically possible to avoid a compromise with slavery in the Constitution, but was it realistic? What is your sense of that?

Paul Finkelman:

Well, I think that there are a couple of answers to that. One is compromises are about a give and take so later in the Constitutional Convention when the delegates from the deep south asks for what becomes the fugitive slave clause which says, “No person held to service or labor in one state under the laws thereof escaping into another shall in consequence of any law or regulation they’re in be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party whom said service or labor may be due.” Notice again, not using the word slave. There’s no compromise here, the northern states don’t ask for a quid pro quo, there is nothing. The South doesn’t give the free states anything, for example, the Free States said, “Look…” The free states could have said for example, “All right, we’ll help you return your fugitive slaves but they have to have a jury trial before we’re sending anybody back to slavery because we want to make sure it’s the right person. We don’t want you to just come here and grab any free black you happen to see in our neighborhood and seize them as slaves. There has to be a process here.”

Or they could have said, “Sure you can come get your fugitive slaves but when free blacks from Pennsylvania, visit Virginia, you have to give them the same rights you give free white people from Pennsylvania, free white people from Virginia you can’t discriminate against our citizens if you expect us to help you keep track of your run away slaves.” Or, alternatively, the northern delegates could have said, “Look, we are not going to be in the business of taking care of your property. If you can’t keep track your slaves, it’s not our fault and no, you can’t come tromping into Pennsylvania and just grabbing people off the streets.”

They didn’t do any of these things. None of these issues were raised in any way and the fugitive slave law clauses is in the Constitution, and later leads to federal statutes. The slave trade provision, why 1800? Why 1808? Originally, by the way, the slave trade vision is supposed to expired in 1800 and then at the last minute they say let’s make it 20 years which, no wait, well, why extend another eight years? If you need slaves, get them now. You got eight years to get them, and then it’s over. The three fifths clause, why not 50%? In other words, these are discussions that could have taken place and didn’t. But this is the other issue. If you’re going to accept that well, there was no choice but to make this covenant with death, disagreement in hell then let’s at least acknowledge it. Let’s put it out there. Let’s talk about it. Let’s be honest about it. Let’s say what we’re doing not try to hide it from the American people.

Or what if you call South Carolina’s bluff? What if you say to South Carolina, “We’re not banning the African slave trade in the Constitution. There’s nothing here that says the African slave trade has to end. We’re simply not going to give it special protection. There is no other import/export business that gets a special clause in the Constitution. You don’t get any special privileges. If you want to import slaves, you can import them and if Congress wants to ban it, then it will be banned.” And if South Carolina says, “Well, we’re not going to join the new constitution,” so what? So be it, so let’s suppose, think about this, let’s suppose Georgia and South Carolina don’t ratify the Constitution and you have a country of 11 states, South Carolina and Georgia are there in the deep south. Spanish Florida is right next door. There are very strong Native American nations in western Georgia and in parts of South Carolina. There’s the Spanish in Florida. There’s the British in the Caribbean. If the British decide to reinvade Charleston, take it back.

The US isn’t going to run it and protect them. Let them go it alone. See how long they last. One of the clauses that I didn’t mention, there are two places in constitution where the national government promises to suppress insurrections. Well, what do you think an insurrection is if you’re a slave owner ?

Greg Kaster:

Right, it’s a slave rebellion.

Paul Finkelman:

All right. So don’t sign the Constitution and when your slaves revolt, don’t expect the US Army or the militia from the next state over to come by and protect you because we won’t. You don’t want to be in? Fine, you’re not it.

Greg Kaster:

So why wasn’t there more discussion? Why weren’t these issues raised and why wasn’t South Carolina’s bluff called I mean, was it just sort of moral cowardice on the part of Northern delicate for the convention?

Paul Finkelman:

Part of it is, I think moral cowardice. I think part of it is a lack of moral compass. That is to say, the northern delegates simply don’t think that this is worth the effort. Part of it is perhaps just a lack of interest. So during the debate over the Commerce Clause, which is very important to northern states, because they want Congress to regulate interstate commerce, all of the southern states except South Carolina, vote no on the commerce clause. Now the Commerce Clause would have passed the convention without the five deep south states supporting it. But South Carolina supports it and South Carolina says we’re supporting it because you supported our interests yesterday, which was bypassing the slave trade costs. So here’s the story, they’re basically saying, we’re willing to sell out African people to get our economic interests taken care of.

We should at least understand that that’s the cost of union and maybe it was a cost too high to pay. During the ratification debates over whether or not to have the constitution ratified, three anti Federalists in Massachusetts complained that under this constitution, they would be forced to protect slavery in the south, that they would have to go to war to suppress slavery values. Now, it turned out they don’t end up having to go to war to supress slave rebellions, they have to go to war to suppress the rebellion of slave owners. But clearly these people understand that the cost of his constitution is very high.

Greg Kaster:

That answers the question I had. So there were at least some, maybe just a few voices of dissent, if you will. I mean, people who spoke up at the convention.

Paul Finkelman:

There are people who speak up at the convention and there are also people who speak up during the debates over ratification in the States, absolutely but they lose. And by the way, when the southern delegates come back from the convention, they all say, “We have a really great deal. This is really terrific. You should support this constitution, because it’s going to protect slavery.”

Greg Kaster:

They understand.

Paul Finkelman:

Yeah, yeah. Patrick Henry who hates the Constitution, he’ll make any argument you can think of to prevent Virginia from ratifying the Constitution. And he says, “Under this constitution, they’re going to come and take your slaves from you,” and Edmund Randolph who’d been at the convention, and refused to sign the Constitution, but later supports it, Edmund Randolph says, “Show me the clause in the Constitution where it threatens slavery.” And James Madison says, “Look at the fugitive slave clause, we have a right to recover our runaway slaves, which is not a right we currently have under the Articles of Confederation.” So they get it that they’ve got a very good deal.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. And then out of this comes not only the union, which will become half slave, half free, but also this pro slavery jurisprudence that is evident in the Supreme Court and that’s the subject of your most recent book, which I highly recommend really a great read, quite interesting and you you reveal a fair amount in that book about Justice Marshall, who’s held up as this paragon of of justice and and his particular pro slavery jurisprudence, but also his buying and selling of slaves, could you talk about that?

Paul Finkelman:

So one of the things that the US has done is to hide our pasts, to live in a kind of a denial about the relationship of slavery to the creation of the United States. Some years ago, when I was a young college professor, I went to Monticello, home to Thomas Jefferson and I was taking the tour of Monticello and I asked the guide where the slaves lived in relationship to the big house in Monticello and the guides started yelling at me, saying, “Why are you asking this? Are you just you trying to destroy the reputation of the great man?” And no, I didn’t ask him about Jefferson’s relationship with his own slave Sally Hemings. I didn’t ask him about Jefferson owning his own relatives. I simply asked the question. “Where did the slaves live in relationship to this house?”

Greg Kaster:

And I think just to pick up and I think at that point thing where you can use the word slaves, or using the word servants or something like that.

Paul Finkelman:

Well, they would have preferred if I use the word servant, absolutely. They would have much preferred the word servant because we don’t want to talk about Thomas Jefferson in slavery. Now for almost two centuries Thomas Jefferson and the people who ran Monticello adamantly denied the Thomas Jefferson had any relationship with Sally Hemings, or that Sally’s children were his children. They did this in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary. But Sally Hemings was the half sister of Jefferson’s wife. Everybody admitted that, that is a man named John Wayles had a family with Mrs. Wayles and he also had a family with Betty Hemings his slave and Sally Hemings was John Wayles’ daughter and Thomas Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles was also John Wayles’ daughter. So Sally Hemings was the half sister in law of Thomas Jefferson. She was his late wife’s half sister. So even if you said, “Well, we don’t know if Jefferson was the father of her children,” you certainly know that Jefferson is the uncle of her children. They are his nieces and nephews.

And the Jefferson family always said, “Thomas didn’t father these children, Jefferson’s nephews did.” So here we have children, who are the blood nephews of Jefferson’s late wife and they are the blood great nephews of Thomas Jefferson through his own nephew’s. So what does it say about a man who owns his nieces and nephews? Even if you don’t want to admit that they are his children, what does that say about him morally? What does it say about American morally? What does it say about a man who says we’re all created equal? We lived in denial, the country lived in denial of this. And by the way, when you went to Jefferson’s house, they never mentioned the word slaves. They talked about the servants. The house servants.

Greg Kaster:

[inaudible 00:42:43]. Yes exactly.

Paul Finkelman:

So now let’s talk about his cousin, John Marshall. Marshall was a distant cousin of Tom Jefferson. Every biography of John Marshall until I wrote my recent book, all said the same thing, that he owned a small number of house servants, a dozen house servants they say in Richmond and that he was not economically involved in slavery, he didn’t buy people, he didn’t sell people. He just had these dozen house servants. Well, actually a dozen house servants is a tremendous investment in slaves. That would be worth a couple million dollars today. But aside from that, I wrote a book on the Supreme Court in slavery, and I started looking at Marshall’s will and in His will, Marshall designates, “I give these slaves to this son and these slaves to this son and I give the slaves over here for my nephew to hold in trust for my daughter,” and I did a little census work and it turns out that Marshall owns about 150 slaves.

He didn’t inherit them like Jefferson. He was given one slave as a wedding present from his father and he later got a few more slaves when his father moved to West Virginia, and didn’t need… moved to Kentucky. I’m sorry, and didn’t want to take all the slaves with him. But otherwise, Marshall bought the slaves. His own record books show him buying one slave after another, constantly buying slaves. And what’s fascinating is, the person who edited the john Marshall papers, never seemed to notice that Marshall was buying all these slaves because when he wrote a biography of Marshall, he didn’t notice that Marshall had all these slaves.

Greg Kaster:

Again, part of the denial.

Paul Finkelman:

It’s the denial. But when I was writing my book, I was talking to one scholar about what I had found and the scholar said, “Are you just trying to destroy the reputation of a great man?” And I said, “No, actually, I’m trying to understand the great man.”

Greg Kaster:

Great answer. And that leads to my next question, which is that you’re pulling in your most recent book, isn’t that this is sort of incidental, but that it is central to understanding Marshall’s jurisprudence, and that the pro slavery constitution is central to understanding even the jurisprudence of Northern Supreme Court jurists who didn’t own slaves and never traffic in slavery. Can you say a little bit about that?

Paul Finkelman:

I’m sorry, I didn’t fully hear you, the connection. Could you repeat the question again?

Greg Kaster:

Yes. In your most recent book, your point isn’t simply that, look at what I found, Marshall traffic in a great number of slaves, but that his ownership is buying and selling of slaves, the fact that he was a slave holder influenced his jurisprudence as a Supreme Court Justice, and that the pro slavery constitution influenced the jurisprudence of even justices on the court, like story of Massachusetts who had nothing to do with slavery directly. So I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that.

Paul Finkelman:

Sure. So again and again and again, this is part of the denial. So if you read the biographies of Marshall, they say things like, “He heard very few cases involving slavery.” One author said that, “He heard relatively few cases involving freedom claims by slaves.” Actually he heard 14 cases as Chief Justice, which is almost one every other year. Now, is that relatively fewer, relatively many, given how difficult it would be for a slave to actually get a case before the Supreme Court. So maybe, in fact, he heard relatively many. But the bottom line is, whenever Marshall wrote an opinion in a case involving a claim of freedom, the slave lost, even if in the lower court, a jury of 12 white men had concluded that this slave was entitled to be free. So, I would say that Marshall has a jurisprudence that is overwhelmingly pro slavery. You’d have to read the whole book to get the full details. But it’s, again it’s buried and nobody wants to talk about it, because it doesn’t fit with the image we want to have of him.

Another Marshall biographer wrote that Marshall decided the cases he decided because he didn’t want to disturb federalism, that he didn’t want to cause a crisis within the union. Yeah, the only problem with that is most of Marshall’s freedom cases are heard before 1820, when there is no national debate on slavery. And in the 1830s, when Marshall was still Chief Justice, and there are cases involving freedom, which Marshall does not decide, but somebody else decides because they’re decided in favor of freedom. This is at a time when in fact, there is a crisis so the other members of the court, including two justices from slave states, write opinions freeing the slaves on the grounds that they’re entitled to their freedom under the law, that they’re not technically, legally slaves and this is not about preventing a crisis in the Union, because there is no crisis in the Union at this time. I’m sorry, but because in the 1830s, they’re not worried about the crisis of the Union. They’re simply saying that, “These slaves are entitled to their freedom and we’re going to decide that way.” So, all the explanations for Marshall are simply dishonest.

Greg Kaster:

They fall apart in the face of the evidence which other scholars have not wanted to confront as head on as you have. What about… just a little bit of a tangent here, what about a justice like Joseph’s Story from Massachusetts, who’s also engaged in pro slavery, jurisprudence?

Paul Finkelman:

That’s right. So the Story’s fascinating. Early in his career, he is pretty anti slavery and he writes an opinion in a lower court case, that is one of the most anti slavery opinions ever written by a federal judge. Later in his career… and then in the 1830s, he writes his great treatise on the Constitution, commentaries on the Constitution. And in commentaries on the Constitution, Story says that the fugitive slave clause was a gift that the North gave the South and in fact, that’s true, because there’s no quid pro quo. And he says, “This shows that the North respected Southern institutions, and this shows that the North was concerned about protecting Southern culture.” Now Story is saying this in the 1830s because it is the beginning of a crisis in the union and Story’s tried to make the argument that, “Hey you southerners, you should love the Constitution.” Then in 1842, he decides a fugitive slave case in which he says that the fugitive slave clause was an absolutely essential compromise of the Constitution and without this clause, the Constitution could never have been ratified.

So it goes from being a gift of the northerners to the southerners, and now has become a central compromise. Well, in fact, it’s not a central compromise. There’s almost no debate over it, Story’s lying and he’s lying, because he’s trying to protect his incredibly pro slavery opinion, which essentially says that southern slave catchers can go into any northern state and grab any person they want to claim as a slave and bring that person back to the south as a slave without any court even determining whether in fact the person’s a slave or not.

Greg Kaster:

Talk about a gift.

Paul Finkelman:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

What explains that change? What explains that? Why that change in Story? If it was a change.

Paul Finkelman:

I think it’s two things. One is that Story is worried about the union and he feels that the only way to protect the union is to give the South everything it wants, which means he’s lost his moral compass. But the others I don’t think Story really cares one way or the other about what happens to black people. Racism and just racial insensitivity.

Greg Kaster:

It’s a terrific book which I urge everyone to read. Accessible even if you’re not a legal historian, the individual story… who else did you do? Story, Marshall and…

Paul Finkelman:

And Tony who wrote the Dred Scott [crosstalk 00:54:24].

Greg Kaster:

Dred Scott, right. Just terrific. You’ve been talking-

Paul Finkelman:

Thank you.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, my pleasure. I loved reading it. You’ve been talking about denial, the denial of history, especially the history of slavery in this country. I wonder if we could turn out the monuments controversy that’s back in the news, especially since the murder of George Floyd here in Minneapolis in May. Thoughts about that, as a historian we should, should all monuments to Jefferson come down for example, or I’m also thinking of the one to Lincoln in DC with the kneeling slave or where some want to take down? Should we care so much about what comes down or care more about what goes up or? Go ahead.

Paul Finkelman:

Well, I think the monuments are complicated. One thing to think about is, we build monuments to honor people and to memorialize events and in the history of most societies, monuments go up and monuments come down. The Nazis built lots of monuments to Nazis. They’re all gone. Right? If you’d gone to Poland and Hungary and Czechoslovakia in 1980, you would have found statues of Stalin and Lenin. They’re all gone. Leningrad is no longer called Leningrad, remember? It used to be called St. Petersburg and then it became Leningrad and now it’s back to St. Petersburg. Well, the Russians were perfectly capable of changing the name of a city twice. Right? There are no monuments to Napoleon that I know of, in France. Nobody, wishes for the good old days when Napoleon tried to conquer the world, and slaughtered a huge population, percentage of the male population of France in the process.

Greg Kaster:

Right or to King George in our own case, our own revolution. A number of monuments to King George III, came down.

Paul Finkelman:

So there’s nothing sacred about a monument. Monuments memorialize. We change the name of streets all the time. We change the name of towns. During World War One, some towns with German names suddenly became [Persing 00:57:06] instead of Bismarck or something like that, right? So, in fact, the British Royal Family changed its name. It used to be the house of Hanover, because the current Queen Elizabeth is a direct descendant of the Hanover family. But during World War One, they changed the name of the royal family from Hanover to Windsor, because they didn’t want to be associated with the enemy, which was German. So countries change names all the time. The military has finally woken up to the fact that it is a little weird to have forts named for people who kill American soldiers, who, in some cases captured Americans. The Confederate generals were fighting against the United States, they weren’t fighting for the United States.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah it’s bizarre that there are statues and statuary hall… that’s finally being removed… it’s crazy, right? What other country does that? Honors traitors.

Paul Finkelman:

Honors traitors. So Civil War monuments are really easy. I think monuments to presidents are more complicated. Thomas Jefferson did many important things in the United States. Thomas Jefferson was president for eight years. He accomplished a great deal. He wrote the Declaration of Independence. One can make strong arguments for honoring Thomas Jefferson in many ways. At the same time, he did everything in his power to preserve and protect slavery. He was the owner of slaves and the protector of slavery and he supported slavery. He spread slavery across the continent and so he’s a very complicated individual. I’m not sure I’d tear the Jefferson Memorial down, but I might redo the inside to say we memorialize this piece of Jefferson, and we condemn this piece, because monuments can also be teaching methods.

Greg Kaster:

Yes, exactly. So the issue wasn’t to keep them up or tear them down.

Paul Finkelman:

No, I think for some it is, I have no problem with tearing down monuments to Jefferson Davis. He was a traitor by any definition of the term.

Greg Kaster:

Right, yeah, I think what you’re suggesting is there’s not one sort of blanket rule or we need to think about to whom the monument is, when it went up, but it’s possible to have a monument that is offensive in some ways, but also stays and gets revised or added to, as you just suggested with respect to Jefferson monument, Jefferson Memorial. Well, I could talk forever about these issues, which I find fascinating and you’re so so knowledgeable about them. But I do want to conclude on a slightly different note, and that is, of course, maybe most listeners don’t know that you are an expert witness in the Barry Bonds home run ball, I think was at a 73rd home runs or…

Paul Finkelman:

73rd home run ball which is the most home runs ever hit by a player in a single season.

Greg Kaster:

Right and you wound up or found yourself as an expert witness because the ownership of that ball was contested, and I’ve just [inaudible 01:01:15] fascinating how you approached approach your position as the expert witness in that case. So, what did you argue?

Paul Finkelman:

Okay, so first set the stage, it’s the last game of the season, Barry Bonds hits… he had already passed Mark McGuire’s record of 70 home runs in one season, and now he has passed 71, 72 on the last day of the season, by the way, the giants are no longer the pennant race so the only reason they voted the game on the last day is to see if Barry Bonds can hit another home run and he does, he hits number 73. It gets into the stands, it’s caught by a guy named Alex Popov, who’s a big Barry Bonds and San Francisco Giants fan. Popov catches the ball and then he’s immediately knocked down by about a dozen people. He’s effectively mugged in the stands, I think there’s no other way to describe it. It’s like a mugging.

Greg Kaster:

It’s all on video.

Paul Finkelman:

Yeah and and it’s all caught on TV newscasts and somebody else ends up with the ball. And so Popov Sue’s to get the ball back. In the meanwhile, I had written an article for a law review on why you own a home run ball if you catch it. Now, for me, this is sort of an interesting intellectual problem. Okay. The home team owns the base, so why is it that when I’m at a baseball game and I catch a ball, why do I get to keep that ball? Why don’t I just give it back to its owner? If I’m at a basketball game and the ball bounces into the stands, I don’t get to keep it. If I’m at a football game and the ball gets kicked into the stands, I don’t get to keep it. So why do I get to keep it if it’s a baseball?

I thought this was an interesting intellectual problem and so I wrote an article on why you own a home run ball if you catch it. When Bonds’ ball was hit, it was caught when there was a controversy immediately emerges, I got called by ESPN to give them a comment and my basic comment was is when the guy caught the ball, it became his ball, he owns it and if somebody else has it, he’s in possession of stolen property. And I ended up being the expert witness in the case. It was a lot of fun and` it’s not every day that you get to do something like this. More importantly, I was also the expert witness against Chief Justice Roy Moore, in his lawsuit over the giant 10 Commandments monument that he put up in the rotunda of the Supreme Court building of Alabama.

Greg Kaster:

I want to ask you about that, before we get to that quickly. So what was the outcome in the Bonds… what did the judge-

Paul Finkelman:

Well, the judge began the case by saying that he’d never been to a baseball game, never played baseball and so he really doesn’t know much about this problem. I thought the judge should have recused himself on incompetence right there. I thought he should have said, “Hey, I’m not competent to hear the case.” But he did hear the case and in what I consider to be a completely astounding ruling, he decided that they should sell the ball and divide it between the two people, the guy who caught it and the guy who ended up with it. I thought it was a horrendous decision, because it essentially counts as violence in the baseball stadium.

Greg Kaster:

That’s a good point.

Paul Finkelman:

And this is not a case of… the fans shouldn’t be fighting with each other, and the baseball stadiums should not be encouraging fans fighting with each other.

Greg Kaster:

Agree. And then the Roy Moore case which I did want to ask you about. Tell us a little bit about that, your position in that case?

Paul Finkelman:

Well, that’s a much in some ways, a pretty simple case. The Constitution says that Congress can make no law respecting an establishment of religion. That clause applies to the states as well as to the Congress that it applies to all governments and clearly a 10 commandments monument is essentially establishing religion in some ways. Because the 10 commandments is clearly a religious monument. That’s what it is. It can’t be anything else. Roy Moore tried to claim that it was a monument to American history, because he said that the 10 commandments was the moral foundation of American law. I was on the witness stand for five and a half hours explaining why that’s utter nonsense and we won that case.

Greg Kaster:

You prevailed, thank goodness. Well, this has been great. We could go on, we’re going to do it again at some point and hopefully you come back to campus. I know you will, when things get back to normal. I really appreciate you taking the time to do this. Good luck with all your work as President at Gratz and we’ll be in touch. Take good care.

Paul Finkelman:

Thank you very much. Have a great day. Stay safe.

Greg Kaster:

We’ll do. Thanks Paul.

Paul Finkelman:

Bye bye.

Greg Kaster:

Bye bye.