Political theorist Jill Locke of the Gustavus political science department talks about her critique of “The Lament that Shame Is Dead” in her engaging and provocative book, Democracy and the Death of Shame (2016).

Season 1, Episode 8: “Shame, Shame, Shame”

Transcript:

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus has produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of Gustavus Office of Marketing. Will Clark, senior communications studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast, and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

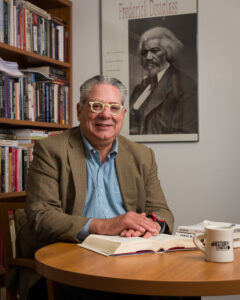

It’s my pleasure to be speaking today with Professor Jill Locke of the Political Science Department and the Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies program here at Gustavus. She currently directs the latter having served previously as Chair of her department.

In addition to her regular teaching, Jill is also an active scholar. She was a fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey during the academic year of 2014-15. And in 2017, she won the Gustavus faculty scholarship award for her extensive and significant research and writing work. She has presented in various venues, both here in the United States and abroad. Jill’s recent book Democracy and The Death of Shame: Political Equality and Social Disturbance, published by Cambridge University Press in 2016, has deservedly garnered, much attention and praise. And we’ll talk about it shortly. So welcome, Jill.

Jill Locke:

Thank you. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. Great to have you. So let’s start at the beginning. If you could tell us a little bit about how you came to be a professor of Political Science. Was that something, for example, you chose to major in as an undergraduate or you came to it in graduate school?

Jill Locke:

I was an undergraduate major in Political Science or actually Politics was the name of our department at Whitman College. And I graduated from Whitman in 1990, with that degree.

Greg Kaster:

Another fine liberal arts college.

Jill Locke:

Thank you. And I don’t think that going to graduate school in political science was something that occurred to me until my senior year when I was in my senior seminar and we had to do an independent research project, a thesis. And I found I really enjoyed the autonomy and the creativity that research provided. But the advice I got… We thought the job market in academics was difficult then. And so I was encouraged to really make sure that that was something that I wanted to do. And I decided not to go straight away to graduate school, but I actually worked in the Admissions Office at Whitman for four years, from 1990 to 1994 and traveled all over the country, talking to students and parents and college counselors, high school teachers, alumni about a Whitman education and the benefits of the liberal arts education.

And during that time, I realized that I really wanted to work in higher ed, that I just, I enjoyed the environment of the college campus. And just the energy and the vitality. And to be… It just seems like it’s an environment where you have a fair amount of autonomy, but you also have all these opportunities for collaboration.

Greg Kaster:

Right. That is really true. That’s well said. That’s right.

Jill Locke:

And right. Just this podcast is a great example of the kinds of spontaneous collaborations that emerge. And so I decided to go and to apply for PhD programs in Political Science. But when I was starting, I did hold open the idea that I would maybe just only get an MA and come back into the college or university environment perhaps in Student Life or Advancement or I wasn’t exactly sure, but I figured I wanted to be in higher ed, so I should go to graduate school.

And I went to Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, the State University of New Jersey as they call it. And I went there really at the advice of my undergraduate mentor and advisor, Dennis Wakefield, and also Tim Kaufman Osborne. At that time I had really only just begun to become interested in Gender Studies. Whitman did not have a Gender Studies Program. And I really only took, I think, one class, Feminist Theory, in the Political Science Department. I think that’s the only class that I took that had anything to do with gender. I was co-president of our equivalent of the Women’s Awareness Center. So I was kind of interested in feminism from a Student Life perspective, but I didn’t really know that much about it. All of this is a long way of saying that Rutgers at that time had just established the first Women In Politics graduate program implement in the US, second in North America. There was one also at York university in Canada.

And especially Tim Kaufman Osborne really said, “I know the people who are running this program, this is a great program. And I think you would be really happy there.” And I went. And I guess the short version is the rest is history. The longer version is that I was able to also study Political Theory at Rutgers, which had a really dynamic program there in the 90s. And so I majored in Political Theory. And then I did my first minor in Women in Politics. And then I did a second minor in Public Law and Courts. So that was… Yeah, that was a really great… So graduate school, as we all know, has its ups and downs, but intellectually, it was a very exciting place to be at Rutgers in the 90s. And there’s a huge feminist community, GWS community there. And I made lifelong friends who I continue to stay in touch with and support each other.

Greg Kaster:

And that story highlights the importance of undergraduate mentoring, and the fact that your professor knew about the Rutgers program and knew that it would be something you would enjoy. And I think we have that. That’s a hallmark of a good liberal arts college. What about courses that you teach? And it’s interesting to you are, do you consider yourself a political theorist? Is that the same as a political scientist? I don’t know.

Jill Locke:

That’s the million dollar question in the discipline. I consider myself a political theorist in a Political Science Department. And, but I was thinking about this, this morning as I was just jotting down some notes in preparation for our conversation. That I’ve actually come… In a strange way, I’ve come to see myself as a political scientist a little bit more in recent years, as wanted to claim the humanistic approach of political theory as a legitimate form of political inquiry. Right. So I think when I was in grad school in the 90s, there was this very sharp divide, understandably so, between empirical political science with the division between qualitative and quantitative. And then theory was just sort of seen as this outlier that barely belonged in the discipline and was being eliminated at a lot of graduate programs. Big R1 research programs were eliminating theory, or really relegating it to just one or two people in a large department of 20 or so.

And I think I inherited that sense of feeling a little bit like an outsider. But as I’ve been working more with students over the years at Gustavus through our own senior research, it’s helped me. And actually through completing my book, it’s helped me to see that we do… We also begin just like historians, right? We begin with a research question. Something that feels like a limitation in the existing accounts. And we come up with some kind of a plan to write about that or to answer that. So there is some kind of a methodology and approach. And we have an answer to that. And it’s not the same as doing large end surveys of 10,000 voters, but I still think that that humanistic approach does get you meaningful answers. And it’s important I think for my students, and it’s important for me and other political theorists to really see us as providing meaningful answers to some of these enduring questions.

Greg Kaster:

And you really… I mean, you know that my colleagues and I in the history department consider you a historian and you’d be… One reason is you pay such close attention to historical context and change and continuity over time. And let’s use this as a transition to your most recent book, which I just think is terrific. I wish we had in fact, a lot more time to talk about it. And what I’ll try to do is post a link to the book with this podcast somehow or record it. But it’s in paperback it’s available, widely available of course, on Amazon, other places. But could you just tell us a little bit about your argument? What do you mean by the death of shame, for example? And what you also call the lament of the death of shame?

Jill Locke:

It is a good transition because the research has been very historical. And I think my current work is continuing in that trend. What I noticed really going back probably 20 years ago, and in some of the contemporary political discourse was this recurring lament that shame is dead, and we’ve lost our way. And this is the… And you hear it from the left and the right, people are too narcissistic they’re too. Self-absorbed, they’ve confused the real issues for personal grievances. Or confused personal grievances for real issues. And that people were not publicly minded enough, not committed enough to the common good. And I found as a historian of political thought, which is a kind of another variation of that-

Greg Kaster:

There you go, that’s a good way to put it.

Jill Locke:

Yes. School of political theory, that this was actually a very familiar refrain. And it bothered me that the existing literature, as far as I was aware, it was really focused just on this philosophical question of is shame… What role does shame play in public life? Is shame good or bad? Does shame help the social fabric cohere? And so on. And I felt like those philosophical debates were missing the patterns in which this lament or this concern about the death of shame had appeared over time.

And I dealt with some of this in my dissertation. I looked at how the lament emerged in the early Christian era. I had a chapter on St. Augustine. And then also looking how Rousseau in the 18th century enlightenment debates, how he lamented the death of shame, and then also Hannah Arendt’s lament. So that was some of the research in the dissertation. And then in the book, I brought in the cases and much more intentionally traced this phenomenon that I call the lament that shame is dead, and try to show how in these different historical moments, the lament emerges as a way of really disciplining and trying to tamp down on fairly radical social transformation or radical transformation of the social and the political worlds.

Greg Kaster:

I think that’s just [inaudible 00:12:57] one of the most important contributions of your book, but yes, go ahead. Sorry.

Jill Locke:

No, no. I was just going to say the cases… So the cases do come from all the way back to ancient Athens, Jacksonian America, the pre-French revolution, and then the school desegregation cases. So all of those are periods where people are talking about political equality in very intentional ways, but are nervous about what it means to use the democratic commitment to political equality to really open up that old specter, right. Going back to panic of post civil war of the specter of social equality.

Greg Kaster:

Right. Yeah. It’s so interesting. But you’re not in the book. You’re not arguing that shame shouldn’t matter. Right? You’re arguing that it does matter. But if I understand you, right, there’s a way to make it matter and not use it to discipline, or dare I say, shame people who are pursuing social equality or other reform or radical agendas.

Jill Locke:

Right. I mean, I think I’m making at least two points. One is, the point is not to get rid of shame. As if we could. I don’t even know what that would look like. Right. Sort of war on shame. I mean, I think there are probably movements that have seen that the desire for more self esteem. But that doesn’t mean that shame goes away. And in many cases the first thing, as queer theorist, Michael Warner says, the first thing we do with our shame is pin it on someone else. Yeah. I’ve come back to that line a lot. Right. So if we’re trying to shed ourselves of our shame, where does that go? I’m not sure where that always goes, but to be aware of the forces that shame and shape our social reality, I think that’s important.

It’s not about getting rid of shame, but really asking us to look at how shame functions and what are our expectations for it. So I think this fantasy that if we just shame people who are behaving in ways that we don’t like, if we just shame them, that they’ll somehow like turn around and be good, decent citizens. I think is probably misplaced desire for what shame can really do. And in fact, the reality is as feminists and queer theorists and psychologists have pointed out that shame can lead to just this, the opposite of upright, moral behavior. And it can make you behave quite badly, right. That’s that pin it on someone else you could harm self, you can harm others. It’s a turn inward.

Greg Kaster:

That’s it. I mean, and it focuses on the individual so much. It seems to me. Or maybe the group too. Missing… Which you get out of the book. I mean, missing systemic, if I can use that word, inequalities that if only, as you said, if only an individual will shape up. Right? Everything will be fine. And of course, that’s not the case.

Jill Locke:

That’s right [crosstalk 00:16:26]. I agree with that completely. Right. It’s highly individualistic. The problem is, you over there, you have no shame versus looking at the social and political context in which that behavior became authorized.

Greg Kaster:

Exactly. See, you are a historian, change over time patterns over time.

Jill Locke:

That’s right. I love history in part, because I think it helps us understand things that political scientists write and think about, but don’t always account for in their broad historical context.

Greg Kaster:

As an undergraduate, I loved political science. It wasn’t the quantitative, it was the qualitative stuff that grabbed me. Would you say a little bit about some of the courses you teach at Gustavus, because you teach both in the Political Science Department, but also in the Gender, Women’s Studies, Women’s Sexuality Studies program as well.

Jill Locke:

I do, I have one course that’s… I have two courses that are sort of crossovers between political science and GWS and that’s Feminist Political thought and also a class called Sex, Power and Politics. That is a 200 level class that puts students in a good position to take that 300 level class in Sex, Power in Feminist Political Thought.

Greg Kaster:

And both of which courses I know from listening to students are very, very popular.

Jill Locke:

They’re courses that I really enjoy teaching and students get to be challenged intellectually, historically, politically, socially. And I think they serve students in both GWS and Political Science well. I’ve tried really hard to speak across that boundary between political science and GWS. I teach a Political Science 160, which is an introduction, kind of like a survey class, titled Political and Legal Thinking. So that’s a major piece of my teaching and I teach a GW. I’ve been teaching, this is my second year of teaching GWS 380, which is actually the capstone for the Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies major. And I also teach a course in Race and Politics In The US or The Politics of Race-

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s another course that I know students really enjoy.

Jill Locke:

Yeah. And that’s the bulk of my current load, but I’ve also taught Ancient and Medieval Political Thought and Modern Political Thought. I’ve taught quite a few different courses in political theory, more traditionally. My research balances those historical questions with also an interest in and race and gender and empire colonialisms with the 20th century topics.

Greg Kaster:

And what about if you, you were meeting with a prospective student, what would you say to that student about why major in Polysci or GWS or both?

Jill Locke:

I would say that Political Science is a great major for students. Well a friend of mine who teaches at Union College, says, “What can you do with X major? Everything and nothing at all.” Right? There’s no automatic prescription. There’s nothing you can’t do with a Political Science major. And there’s nothing that a Political Science major automatically… It’s not like Pharmacy or something where you walk out the door and there you go.

So in some sense, my answer for Political Science would be my answer for almost any major. And I always encourage students to major in whatever they find passionate and that they’ll figure out the career path along the way. But if a student was like, “I love Political Science. I want to major in it. Can you help me better understand why? What I would do with that? Or what do other students do?” I think that Political Science, I like to say it’s all kind of like a little micro liberal arts education in itself in that we would be introduced to some quantitative methods. You would be introduced into history and philosophical thinking. I think our department covers almost every one of, or many of the general ed areas in the liberal arts perspectives.

Greg Kaster:

Your department is similar to ours in that respect.

Jill Locke:

Yeah. Right. We have a theology, religion class, Religion, and Politics in America. We have a lot of our faculty teach in the first term seminar departments. So I think there’s a real commitment in political science at Gustavus to mentoring. And back to your point from earlier in our conversation, and that I think that’s extremely important. Our classes are reasonably sized. So you get a lot of one-on-one attention. They’re both domestic, US perspective, and also global. We encourage our students to continue with their multiple language study, to study away, to understand, how to read and interpret data so that you’re not misled by studies. And also to think critically about straightforward accounts of what the facts say or what history tells us. And to see these things as open. And I think all students should take political science because I think it’s very important that we have a sophisticated understanding of the political world and what it means to act and move in it.

Greg Kaster:

Certainly agree. Strongly agree. You attended a liberal arts college, which I did not. I attended a big state school and then a big private university. What are some of the rewards of now teaching at a liberal arts college?

Jill Locke:

I think one of the greatest things is really the collegiality among the faculty. So at a big university, you’re going to have the Political Science Department is going to take up two floors of a major… So even just right down to the physical space. I share a photocopier with colleagues and Classics, Religion, Philosophy in addition to Political Science,

Greg Kaster:

The copy machine is an engine of collegiality and interdisciplinarity.

Jill Locke:

It is. You just get a chance to check out, “Well, what are you working on? What do you copy? Oh, that looks interesting.” And when I was working on my book and had decided to include the section on ancient Greece, I relied on informal conversations I had with people like Yurie Hong, Sean Easton, Matt Panciera, Eric Dugdale in the Classics Department. And just realizing that we’re all kind of in it together. And we’re all answering. Sometimes we’re reading the same text, but from different perspectives or different emphases.

Similarly I’ve become good friends with several people in the Spanish section of the Modern Languages, Literatures and Cultures program. And I’ve learned so much from Carlos Mejia Suarez about the Columbian novels, the post-conflict novels that he does his research on. I’ve learned so much about LGBT life in Spain and culture in Spain, from Dario Sanchez-Gonzalez, two friends there. And I just think in a bigger university, I literally wouldn’t have the time and space to make those connections. And I bring those informal conversations that I have with colleagues in other departments, I bring them into my own political science classroom. They inform how I think about the world and-

Greg Kaster:

That’s exactly what I was going to say. And it enriches our teaching. I couldn’t agree more.

Jill Locke:

Absolutely. And I think I didn’t know about how that played out for my professors as a college student. But I certainly felt it as a student. My senior year, my roommates, I lived with two English majors and another Polysci major. And all our books were piled up on the coffee table in the living room. We talked about what we were reading and doing. And I just, I love that kind of intellectual cross fertilization.

Greg Kaster:

That’s the best part of higher ed, the best part of our work. Well, it’s been great to talk to you. We have to do this again because I’d like to hear perhaps in another podcast about your current work. And thank you so much.

Jill Locke:

You’re welcome. Thank you.