Bryan Messerly, interim director of the Gustavus Center for International and Cultural Education, discusses bringing students abroad home safely during the COVID-19 pandemic and the life-changing potential of study away experiences.

Season 1, Episode 4: Journeying Inward by Journeying Outward

Transcript:

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus is produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of the Gustavus Office of Marketing; Will Clark, senior communication studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast; and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus has produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of Gustavus Office of Marketing. Will Clark, senior communications studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast, and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

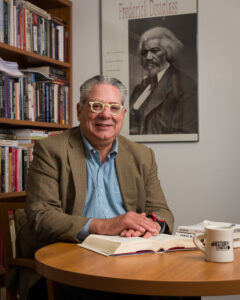

What is the value of study abroad as part of a Gustavus education? What opportunities are there for Gustavus students to benefit from study away? And what happens to study away programs and students when a pandemic like COVID-19 takes hold? No one is better suited to address these questions than my guest today, Bryan Messerly. Bryan is interim co-director of the Center for International and Cultural Education at Gustavus. Prior to that, he worked on the US Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs on the Fulbright program, the US government’s flagship educational exchange program. His knowledge about international education is unparalleled on our campus, and it is my pleasure to speak with him about that topic today. Bryan, welcome to the podcast.

Bryan Messerly:

Thank you. Yeah. Glad to be here and looking forward to talking about this.

Greg Kaster:

Thanks. Before we get to your story and how you came to do what you’re doing, let’s just jump right into the present. You were on duty, so to speak, when the pandemic hit. Could you talk to us a little bit about, tell us a little bit about what that was like, what you had to do, what the students had to do. I don’t know how many… You know, obviously, how many students we had abroad, but we had numerous students abroad. What was that like as this pandemic began to develop?

Bryan Messerly:

Yeah. Certainly. So, yeah, it’s been quite the 2020 so far. Really, I mean, this virus came onto my radar late in 2019, and at the time, made a note of hearing about it, that something was going on in China. And with other past viruses that have popped onto our radar, have not always made the jump to being a pandemic, and so it wasn’t necessarily that, at that point, I was thinking that we were going to get to where we’re at. But I don’t think many people were at that point. But as it started to develop in late January, we had a lot of January term programs that were out around the world, and we started to see more and more information about what was going on in China and then started to see some cases that started to show up in other countries as well. But not really much data or evidence of local transmissions.

So, at that point, though, I was definitely starting to get a little bit more concerned. It started to impact a little bit on our programming as we had some students who were in Vietnam who had return flights through China, and we had to reroute them just out of an abundance of caution, because we weren’t sure if transiting through China would be difficult for them to get back into the United States. And so, that was the first action that we had to take. But then, it became, at first, a slow moving series of decisions that gradually accelerated, and by the middle of March, there was a week in the middle of March that felt like it was a full month because of everything that was happening and how quickly we were making decisions.

But yeah, I was looking back at my email the other day, and I realized that as we were getting new information, we were trying to communicate with the students, and there was one 48 hour period where I sent a message reassuring the students that we’re still monitoring the situation. And at that point, things looked like they were still okay for the students to remain in their study away sites. And then, within 48 hours, I was sending another email saying everybody needs to come home because the State Department and the CDC had elevated their warnings to unprecedented levels for the whole globe. So, in some ways it was not a hard decision because, at that point, it was clear that this is what we had to do, so it was an easy decision in that respect. But it was still a hard decision in the fact that I knew that this was going to be devastating for most of the 41 students who we had out around the world.

And I found that for many of them, it’s been a really emotionally conflicted process in terms of going from participating in this transformative, life-changing study away program to needing to readjust what they were expecting for the rest of the semester. And so, many of them, they looked at that, and some of them were, I think, at that point ready, because, obviously, this has been something that has not evenly hit every country at the same time. There’s been a lot of… One country, like for example, Italy was well ahead of everybody else in terms of their viral curve. Whereas, other countries like, say, New Zealand, have largely been spared from the worst impact of the virus so far.

And so, people were seeing different things locally and it made it, I think, a little bit… Some of them were, I think, maybe a little bit surprised that everybody was coming home, but then as the next couple of weeks progressed and we saw more and more airline cancellations, border closures, travel restrictions, the severity, I think, became clear to everybody. But that said, even though people and the students who are abroad, I think, understood what was going on, it’s still difficult because they’re dealing with this sense of a significant lost opportunity. And for that, I think, they’ve handled it well, they’ve handled it with a lot of grace and maturity and courage, but yeah, it was a difficult transition from them to make.

Greg Kaster:

I studied abroad as an undergraduate in Mexico for a semester. Right? I think you raised a really important point, which is maybe easily overlooked, or too easily overlooked, which is the emotional investment of the students in that experience. And yes, I mean, students are going to miss in-person graduation, but they’re also going to miss that extraordinary opportunity. Maybe some of them who will continue at Gustavus will have the chance, we hope, this coming year. You worked for the Fulbright program. How did you find your way to this particular work? Well, even earlier, what’s the trajectory, let’s say, from your undergraduate education to where you are now?

Bryan Messerly:

Yeah, certainly. And I wanted to follow up on what you were saying, too, because I think that was a really great point. I’ve heard from a number of students who have told me that they felt like they had not finished what they set out to do, or various variations on that. And what I’ve been telling students is, they’ve had to confront something that is a generational challenge. And so, they didn’t get the experience that they expected, but I think they’re definitely getting a different experience and they’re learning and growing from that. But you’re absolutely right. Psychologically, it’s difficult when this is a major thing that many of them have been looking forward to many, many years, and to have it cut short is really difficult.

So, as far as my trajectory, yeah, when I was a senior in college, I took the foreign service exam, and at that point, I was really interested in international relations and diplomacy, even though I was a English and Italian Lit double major as an undergrad at the University of Kansas. But for me, I think one of the things that happened is some of my literature courses were looking at comparative elements, but also some of them were related to questions like international relations or global conflict, and so that sparked more of an interest in looking at the wider world. And I also, my generational moment was 9/11, and I remember my reaction to that was very much that I felt like the solution to some of the problems that we’re facing the world at that point, global terrorism and conflict, intractable conflicts, a lot of that was actually the solution wasn’t necessarily forced but it was actually building better relationships and better communities around the world where that type of ideology wasn’t going to appeal to people.

And so, I took the foreign service exam. I did not get selected, obviously, but then, I ended up going first to graduate school for a Master’s in English at Boston College. And then, afterward, I did a master’s in… It was called Ethics, Peace, and Global Affairs, but it was a conflict resolution, international relations degree that had a lot of courses in the Philosophy Department related to ethics.

Greg Kaster:

Was that at Boston College also?

Bryan Messerly:

[inaudible 00:11:14] yeah, second master’s was at American University in Washington DC.

Greg Kaster:

Okay.

Bryan Messerly:

And the nice thing about doing a Master’s in Washington DC is, it’s a lot easier to do internships. A number of people who are interested in Washington DC will go and do an internship over a summer, and so if you live in DC, you can tell it’s internship season because all of a sudden on the Metro you see all these young people in ill-fitting suits who are looking very sleep deprived, getting up at 7:00 to get on the Metro, and you know that all the interns have arrived. But if you’re a students enrolled there at one of the colleges, it makes it easier because you can do a semester length internship, and you can do it while you’re still taking classes. And so, I did an internship in the Bureau of International Organization Affairs at the State Department.

And then, after I graduated, I got a job in the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs working on the Fulbright program, and for me, the connection with all this is I’ve been interested.. I’d actually spent a few years teaching Italian after I graduated from Kansas. And so, for me, the connection was I had an educational background and the Bureau of Educational Cultural Affairs, obviously, is dealing with education. But the key focus is exchange, bringing people together from different countries, and the mission of the Fulbright program, the vision, when Senator Fulbright of Arkansas was building this program and proposing the legislation for this program, was that the best way to create a more peaceful and prosperous world was that we’d have to know each other, we’d have to work together across cultures. The Fulbright program allows people to go from their country to the US and study or for people in the US to go to countries around the world and study or research, and with the idea that that’s going to create linkages that will help us to solve the world’s problems better.

So, for me, this was bringing together multiple interests and passions of mine, and so that was a great opportunity to learn more about exchange and international education. And then, my wife is in the History Department, and so when she got her job at Gustavus, there just happened to be an opening in the Center for International and Cultural Education at the same time, or a little bit afterward that I applied for. So, that’s how I ended up at Gustavus. But yeah, I didn’t know that this was where I was going to… like the trajectory that my career was going to take. But it’s interesting, the things that you do end up piecing together in ways that you don’t necessarily expect, but they give you opportunities once you are out in the workforce.

Greg Kaster:

That is so true. I think so many students, perhaps some parents assume you major in this and that’s a direct line to that, but it’s just so often not the case. And all these other experiences do bear fruit in sometimes very direct ways, but often in indirect ways as well, unplanned ways, unanticipated ways. You’ve touched on this already a little bit in your previous answer, you’re answer in my previous question, but could you say a little bit more about your vision of how study away, international education in particular, fits in a liberal arts education like that provided by Gustavus? What is important about studying abroad to an undergraduate, or what should be important?

Bryan Messerly:

Right. Yeah. That’s a great question, and it’s something that I end up talking to students and parents, especially prospective students about quite a bit. For me, study away works on different levels. There is the very practical, pragmatic level of it’s going to teach students to be more flexible, more adaptable. They’re going to understand how and be able to thrive in situations of ambiguity, because when you’re in a different culture, and especially if you don’t speak the language, you’re oftentimes not going to necessarily know what the right answer is or what’s going on. And you have to become comfortable sitting in that space and understanding how you can react and behave to be successful. So, on one level, it prepares students for whatever career they’re going to do. And this is why data in our field shows that all things being equal employers to favor students who have had some type of international experience, whether it’s study away or an internship abroad or something of that nature, because it demonstrates the students have… To survive that experience, they’ve had to have some flexibility, adaptability, and just understanding of how to deal with ambiguity.

It also provides a number of other skills, intercultural communication, and that’s something that employers will also prize, especially in this modern world, where it doesn’t matter what job you do after you graduate, you’re going to be interacting with people from different backgrounds. Whether you’re going to be a nurse in rural Minnesota or you’re going to be working for one of the big multinationals up in the cities or going off and doing a policy job in DC, you’re going to work with people from backgrounds that are different from your own. And having gone abroad, whether it’s to an anglophone country or whether it’s to a country where you don’t even speak the language, you learn how to communicate better. You have to learn how to operate in that space where you don’t always necessarily understand everything, and you have to learn how to communicate with different styles and within different cultural contexts. And so, that’s another skill that students learn that’s very helpful.

And then related to that, of course, is foreign language. So, there’s all of this practical stuff that students gain from studying away. But then, I also talked to them about the intangible things that are, I think, really at the heart of the experience. Joseph Campbell talks about the Hero’s Journey, and he talks about how the whole point of the hero’s journey is actually internal. You go out to the ends of the earth, but what you’re actually doing is you’re going inside, you’re going deep into your own interior, because when you get out of your own cultural comfort zone, your own bubble, you’re forced to grapple with who you are. And it’s something that we take for granted, but when you’re dislocated, it gives you that opportunity to explore who you really are, what your values are.

So, sometimes people think of this as, I’m really changed from my city away experienced, and I think that, in many cases, what they’re actually experiencing is they actually have had a chance to consciously focus on what is it that is important about my culture? What’s important about my identity? And so, it’s a great opportunity for students to really learn about who they are and how they fit into our increasingly global world. And so, that’s, I think, that element, when students talk about, “It changed my life,” or, “It was transformational,” I think that that’s something that you hear it from most students who study away that this is really a transformational moment. But a lot of that is because, by going out, they’re ending up going inward and looking at who they are, and they get a better sense of that. So, that’s, I think, really a crucial piece of this.

And then, the last piece that I want students to get is I want them to see how their home community is connected to communities around the world and to have an ethical and better… just a framework to understand how decisions that they make in their own community, or decisions that people make in communities around the world, impact people in other places. And so, I want them, when they study away, to think about, what is their role as a visitor in this society? What privileges do they have by being able to do this? And then, to think about what responsibilities they have as they go home, in terms of sharing some of the things that they’ve learned and helping people understand the culture that they’ve visited.

And then, when they’re in the country that they’re visiting, helping those people understand their own home culture and understand Americans better. Because oftentimes, we feel like we’re much more connected, but it’s all mediated through the news and sometimes Hollywood movies. You encounter stereotypes that people have of Americans, and then, of course, Americans have of different cultures around the world. And so, it’s an opportunity for students to help break down some of those and create a better understanding across cultures.

Greg Kaster:

That’s just a great summary of, or a great case, for study abroad, and I really like the way you break it down. And then, of course, they overlap, the practical or pragmatic and the intangibles. And as someone as an undergraduate who studied in Mexico, Central America… or Central Mexico, the intangibles were definitely what I remember most and what changed me the most. In the few minutes remaining, would you offer us some sense of the opportunities available to Gustavus students for study abroad, in particular international education? Not necessarily specific programs, but just places they go. And by the way, roughly, what percentage of our students do a study outside of the country?

Bryan Messerly:

Yeah. So, it’s about 50% of any graduating class. Obviously, that fluctuates up and down by five percentage points, more or less. So, it’s, I feel, a good number for a small liberal arts college. It puts us in a position where, when you’re looking at senior classes, a one and two students should have some international perspective that they can bring to the material, which I think is… yeah, I think is a great opportunity even for those students who don’t go abroad because they get to benefit from that experience. And I think that, especially in a liberal arts model, and where professors are generally thinking about being interdisciplinary or cross disciplinary or at least having students draw on their other classes, it gives a lot of opportunity for those professors to draw in on some of that experience. And just anecdotally, I know that happens quite a bit on campus, that type of synergy, which is exciting.

So, as far as the types of opportunities that we have, so those roughly 50% who study away, a little bit more than half of those will do a January term program. So, probably maybe 60% will study away during a January term faculty-led program. And these are programs that are generally two to four weeks. Sometimes they have a little bit on campus, but they’re led by a Gustavus faculty member or a couple of faculty members. And they take students all over the world. We’ve been really fortunate in having really good geographical diversity of these programs. We’ve had students study on every continent except for Antarctica every January, or at least most Januarys, and maybe there’s one where we miss one continent. But there’s always a good range of geographical options for students.

We have some domestic options, which appeal to some students who, for whatever reason, it might be difficult for them to study away or study outside of the United States, and sometimes they just look at those topics and the topics are really exciting. January term is definitely one of the big times when students will study away. Then we also have semester length programs, and those can either be through an exchange with one of our exchange partners or it could be through a third party partner that we work with. And these are all programs that we sponsor, so they’ve been vetted. And these range from doing language immersion to intensive research, some of them will have an internship component, some will be based on a theme or a topic, and others will be more just general and they’ll have opportunities to take a range of courses at a local study center, or maybe they’ll take some classes at a study center and then some at a local institution there.

And so, that makes up most of our study away, the semester length or the J term, but we have a few students who will study for a full academic year. We have some who will study over the summer, and that number has grown in recent years. So, these are all different opportunities, and when I talk to students, I always mention that the reason we have a wide variety of opportunities is because people are going to have different motivations and different goals for their study away. And in some cases, a student who has never been abroad before, sometimes who has never been… We’ve had students who have never been on planes before, and in those cases, maybe doing a program with a faculty leader is a good place to start because you have a little bit more support. Whereas, other students who have done a lot of travel really would rather be much more independent and doing a semester program with a provider where they have a lot more independence and they have to do more on their own, might be more appealing to them.

And then, as far as locations, students go really all over the world, both for January and for semester length programs. And so, it’s really exciting to know that we’ve had students, obviously, who study in Western Europe, but we’ve also had students studying in Jordan, in Cambodia, Vietnam, all through South America. So, that’s exciting that we’re getting students really out into all different types of communities around the world and that they’re bringing that knowledge back to Gustavus.

Greg Kaster:

I agree. It’s exciting, too. It’s exciting as a professor to have some of these students in our classes, and it really is, as you’re suggesting, it really is an international program, global, dare I say, like the pandemic. But thank you so much for providing all this information, these perspectives. I hope in a future podcast to speak with some students who’ve gone abroad and who can share with us some of their experiences. And also, I should mention, when you referred to your wife in the History Department, that is of course our dear colleague, Professor Madelina Marinari, with whom I did a podcast recently about her work on immigration history. So, Bryan, thank you so much. I’m glad the difficult task of making sure all our students returned safely is behind you, and you did a great job on that, by the way. We all know. And take good care.

Bryan Messerly:

Yeah. Thank you. Thanks for the opportunity, and yeah, take care and stay safe.