Professor Amy Seham of the Gustavus Department of Theatre and Dance talks about researching and performing improv, social justice theatre, directing in an educational setting, the benefits of majoring in theatre, this spring’s play on campus and adjusting its production due to COVID-19.

Season 6, Episode 1: Curtain-Up!

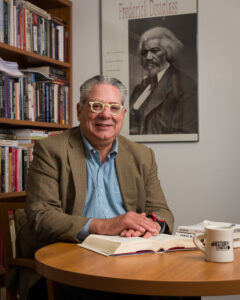

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus is produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of Gustavus Office of Marketing. Will Clark, senior communications studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast, and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

In preparing for today’s conversation with my colleague Dr. Amy Seham of the Department of Theatre and Dance at Gustavus, I came across a 2017 Q&A with the then grade 11 Dean and varsity girls’ hockey coach at the Blake school in Minneapolis. Asked by a Blake publication what teacher inspired you the most and how? He responded, “Amy Seham from Gustavus. I took her beginning acting course in the second semester of my senior year to fulfill my arts participation requirement. It turned out to be my favorite class and contributed to my life philosophy of yes and.”

This would come as no surprise to anyone familiar with Amy’s compelling and provocative work as a teacher and director of theatre at Gustavus, where she has taught since 1997, and annually directed outstanding productions of both well-known and new plays across the genres.

Amy earned her BA in theatre in English from Wesleyan University, her MFA in theatre directing from Northwestern University, and her PhD in theatre from the University of Wisconsin Madison. She’s an expert in the history of improv and theatre for social justice. She wrote about the former in her groundbreaking 2001 book, Who’s Improv Is It Anyway. And she both teaches a course in the latter and mentor the acclaim, though now alas disbanded, I am, we are student troop at Gustavus, which performs skits during new student orientation about such topics as racism, hetero-sexism, and sexual assault.

Amy is also a playwright whose work has been featured and well received in the Minnesota Fringe Festival. And she has conducted workshops around the US and abroad. Her work in the classroom, onstage, and in print is terrific, as well as timelier than ever, given our present historical moment. And I’m delighted to speak with her about her work for the podcast. Welcome, Amy.

Amy Seham:

Thank you. Wow, what a great introduction. I appreciate it.

Greg Kaster:

Oh, my pleasure. Yeah. I’ve always wanted to talk to you. I mean, one of the things about doing this that I’ve said before is the chance to talk with colleagues about their work, because usually we just see each other in passing or on a committee.

I’ve never been on stage I guess other than… Oh, I did tap dancing once, I forgot about that. I’ve repressed that memory, when I was [crosstalk 00:02:36].

Amy Seham:

Wonderful.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. Oh, God, it was a sombrero, the whole thing. It was crazy.

Amy Seham:

Oh my goodness.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. But anyway, I guess it was the Mexican hat dance. In any case, absolutely fascinated by the theatre, and acting and directing, what little I know about it, all of which is why I’m anxious to speak with you, in addition to the social justice dimension of your work. As you may know, I haven’t taught in a while, but I teach a course on the history of American radicalism, and we do look a little bit, and in the 1930s too, we look at a little bit of theatre in those courses, and social justice.

But in any case, I like origin stories, so start with that. Where are you from? Where did you grow up? And how did you find your way to Wesleyan? A great liberal arts school. And the theatre.

Amy Seham:

Well, I’m from New Jersey. I was born in New York City, but my memories begin in Tenafly, New Jersey from age three, I think on. I’ve always loved theatre. My mother’s parents did community theatre and academic theatre. My father was a lawyer. My parents met at Brooklyn High School. And they were both in some of the little shows that they would do in something that’s apparently famous in some quarters called Sing, that they did in the high school there.

In any event, there’s old photos of them both in a skit from that though. My mother did theatre at Mount Holyoke, she was the lead.

Greg Kaster:

Wow.

Amy Seham:

Yeah. Good Person of Szechwan. There’s just been a lot of theatricality in the family. And when I was a kid, I’m the oldest of four, I would organize my three younger siblings into little shows that they perform. And I remember doing the Emperor’s New Clothes, and having my youngest sister who was maybe three at the time, she had one line, “The emperor has no clothes.”

Greg Kaster:

And did you make her repeat that over and over again? You were top director even then I bet?

Amy Seham:

Yeah. I got started pretty early, doing that stuff. I got to Wesleyan and I remember touring some of the Northeast schools, which growing up in New Jersey, the snobbish attitude was that that was really the only place to go. I actually stepped onto the stage at Wesleyan and just loved the newish theatre that they had there.

Since they had the new theatre, the old theatre had been turned over to the students who had a very active season of student directed plays, which I took advantage of when I got there. And I was just doing theatre all the time. And one of the things that was my experience is that I wouldn’t get cast by the mainstream directors, the faculty directors. I wasn’t the look they were looking for or I’m not sure what it always was. So I had to create my own works. And I created shows for myself to be in, a lot of sort of cabarets, where I would sing with someone else or a few other people.

And then I started feeling more ambitious about the directing aspect of it and realized that I couldn’t really be in the show if I wanted to have more perspective on the show, to make it successful, so I started just directing.

Greg Kaster:

I mean, could you take classes in directing at Wesleyan? Is it something you studied?

Amy Seham:

There was one course in directing. There were acting classes. There was a playwriting class. And actually, I do have a bizarre little anecdote because I feel like the course of my entire life was shaped by one bad answer to a question that I gave years ago. Because I was very, very active doing this student theatre, and I really, I directed a show for the student theatre every semester I was at Wesleyan, except the very first semester.

I ended up doing that rather than assisting a faculty person director, or being an extra in one of their larger productions. And I was looking at the bulletin board and there was an announcement that one of the faculty was giving a rehearsal techniques class. But it was at the same time as another course in Shakespeare, I think, that I was very interested in. And so this faculty guy was behind me, and I said, “I don’t know which one I should take. I’d like to do rehearsal techniques.” And he said, “You? What could you possibly learn?” And I said, “Well, you’re right. I’m going to take the Shakespeare.”

I was so clueless that I didn’t realize the just sort of dripping sarcasm with which he had said that and the way in which I deeply offended him by not getting it in that moment. I really didn’t have mentorship. I mean, I really I wasn’t doing the admiration or just the bring me coffee kinds of things that they thought students should be doing. I chose to do my own show, do my own show, do my own show, but when I left Wesleyan, it mattered to some degree, I didn’t get any support from that faculty in my next endeavors. And I think too, just being a woman in 1978-

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I was going to ask about that. Yeah, it had to have something to do with it.

Amy Seham:

Yeah, I’m sure it did.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. These plays you were doing at Wesleyan, you would do them on your own? I mean, then what? Invite people to come or?

Amy Seham:

Well, I mean we had something called second stage at the 92 Theatre, which was the old theatre building, and it was very well organized. You got elected to the board of it, and you applied for a week and when you’ve got a week, you got Sunday night through Saturday night, I guess, or Sunday through… You had a week in the theatre. And you came in, you put your setup, you text it, rehearsed it, opened, had three performances, tore it down, the next person was already waiting to come in and do theirs.

Greg Kaster:

That’s intense.

Amy Seham:

Yeah, it was very intense, but it was a great opportunity. And there was sort of an overarching sort of tension between how active that was and what the department faculty were directing, because they had a very hard time getting people to do walk on types of roles. And I have a little more sympathy for that now than I had when I was a student, because I certainly might look at a student production here and say, “Well, okay, but I hope I have enough people to do the main show that we’re doing here.”

Greg Kaster:

Now, were you already interested in social justice issues and social justice theatre at that point?

Amy Seham:

I was definitely tuned into feminism at an early age, my mother was extremely active in the feminist movement. I remember as a teen, as 13 years old, I think my mother was very turned on. I mean, it was a discovery for her. It was a new event in her life that changed the course of her life. And she was talking about this, that, the other, and the chair person of something. And I said, “Chairperson, that’s stupid. That sounds so dumb. Are we going to say person whole cover, mother? That’s just dumb.” I remember having that conversation.

Today, I mean, we don’t say chairperson, I think. Well, some people do. It’s like, chair. So it wasn’t easy for me to have my mother suddenly say, “I shouldn’t have to do the laundry.” “What are you talking about?” So [inaudible 00:13:45] was exposed to all these ideas. Yeah, my mother founded a Women’s Rights Center in Englewood, New Jersey, and she’s got recognized by New Jersey Governor. She was she really had an impact in the world.

Greg Kaster:

I mean, both the theatre and then social justice are really in your DNA metaphorically speaking I guess. Yeah. From Wesleyan, you went on to Northwestern. I don’t know if I’m right about this, you know more, but has a very good acting theatre program. Of course, Chicago, home to Second City. What was it about Northwestern the attracted you?

Amy Seham:

Well, yeah, all of that. I mean, it is kind of interesting that even at Wesleyan, I was involved in a little student improv troupe, and that’s very early, actually, to be in the 70s doing improv. Because today there’s an improv troupe at every college campus, but then it was actually pretty new.

So I already had that interest from Wesleyan. And when I went to the Chicago area, obviously, the improv is there. I actually had a struggle at Northwestern because I went immediately after undergraduate. At Wesleyan, we were very kind of conceptual and experimental. And we’d say, “What show are you doing? Oh, what’s your concept?”

And at Northwestern, my joke is that people would say, “Who’s your agent?” A very different attitude about what people were doing and why they were doing it. And I just didn’t really fit in. So it was difficult for me, but I was chosen to direct a winning play of the playwriting contest, which was a musical about the relationship between an African American young woman and a white young man who both had applied to the same medical school, and she got in and he didn’t, but he had better grades. And there was a tension around that. That was a very intense experience working with this interracial cast around a racial issue in 1980.

At one point, I think there was a school newspaper saying, “The only people who are really talking to each other across race are the people doing this show.” That was interesting.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. Have you ever done that play again? I mean, that sounds like a play that could be done today.

Amy Seham:

That’s a good point. No, I have not. I’ve lost track of the playwright. I think it would be good to track her down. I think it was really well done. The lead male was Michael Greiff, who went on to direct Rent-

Greg Kaster:

Oh, yeah.

Amy Seham:

… [crosstalk 00:17:38] New York. And I’ve always thought, “Well, if I had very wealthy parents [crosstalk 00:17:45] would have been able to do that too.”

Greg Kaster:

I want to talk about your book, Who’s Improv Is it Anyway, which is just terrific. It’s an important book, recognized as such by people in the field, by your peers. But so were you already kind of at work on that while you were at Northwestern or did that wait until you [crosstalk 00:18:09]?

Amy Seham:

That was part of my collected experience of improv, but not for quite some time did I think about writing about it. I went through another couple of phases in my journey and had this theatre company in New Haven where we were doing original work, and I was doing feminist plays, but also big outdoor productions of Shakespeare. And I used improvisation to create some of my original works. And there were some young men in particular, who got involved with us and said, “You know this improvisation stuff, we should be doing in improv comedy show. Or can I get the phone numbers of the people in your improvisation class? Because I’m going to put together an improv comedy troupe.” And I said, “Well, no, you can’t have the phone numbers of the people that I’m working with, but you can do an improv troupe under the auspices of our theatre. How about.”

So this improv troupe was formed and I was in it. And there were some really good times, but there was incredible sexism. I was bewildered because I was using improvisation to create, collaboratively, these… I had a play called Oops, I Forgot To Get Married, about being a single woman. I had a group of eight women that we would get together and talk about what it was like to be a woman, and then we’d improvise scenes, and then make this play together. I did a number of those kinds of projects.

To me, improvisation should have been a comfortable way to work. And in fact, I was constantly feeling left out or pressured or sort of bullied. And that group ended up sort of… We kind of ended up parting ways with that group over some, I think, pretty sexist stuff that we’re doing.

Greg Kaster:

I can tell you’re trying to say it in a nice way.

Amy Seham:

And so then, fast forward to coming up with an idea for a dissertation-

Greg Kaster:

At Madison.

Amy Seham:

… at Madison. And I said, “I’ve always wondered how does improv get so sexist? Why is it so sexist when everything that Viola Spolin wrote was about support each other and collaborate, and all of the rhetoric around improv is about equity and mutual support and so forth.” And I said to my advisor, “I want to write about how improv is so sexist.” And she said, “Everything’s sexist. Why is that news? Why is that of interest, because it’s self evident that things are sexist.” And I said, “Well, it’s because the claim for it, the way it’s talked about, the way it’s promoted is always about how egalitarian it is and how communal it is. But that’s not what really happens. Or my experience is that it’s not what really happens, but I don’t think I’m alone in that.”

And actually, once I really got into the research, and was going from Madison to Chicago, very often, driving back and forth, and interviewing women in Chicago who did improv, I got so much material from women who said, “Oh, my God, yes. I have a story for you.” Or, “Yeah, this is our lives.” And some of the best people who’ve been involved have left the field because they’re so fed up with the way women are treated.

And so it was a very rich field to be researching. Fast forward again, when I published the book, there was all kinds of reaction. I had comments on Amazon and so forth, everywhere from, “Thank God, someone’s finally talking about this. This is exactly what I’m experiencing.” To, “She doesn’t know what she’s talking about. She clearly doesn’t understand improv. It’s clear she has her own personal issues and problems that she’s dealing with.” So I got these four or five star things, and then these one star, or, “Thanks for the book.”

Greg Kaster:

Well, you were pulling back the veil, and that’s going to generate some comments like that. I mean, I was thinking about this today, getting ready for our conversation, your book isn’t the feminine mystique, I understand, but in a way, you’re doing the same thing, you’re naming a problem that everyone is experiencing. You’re identifying it but kind of not talking about it. I can just imagine some of the women just feeling great relief and pouring out their stories.

Amy Seham:

That’s true.

Greg Kaster:

Were you interviewing people from Second City or not?

Amy Seham:

I did interview some people from Second City. I mean, one of the things that happened is that I came into the research with the intention of learning more about how gender works in improv, and why I’d had the experiences I had had. But what I learned when I was doing the research is that improv had evolved into a whole art form that had many different layers by now. Second city or the compass starts in 1955. But it’s sort of by the 80s really that there’s improv-Olympic, which does a whole other form called Long Form, and then proliferated all these other teams. And then lots of independent little improv troupes. It’s just it’s gotten exponentially larger every year.

And meanwhile, there was this British improv guru, who had independently invented his form of improv because the Chicago improv is based on Viola Spolin’s work. And Johnston, Keith Johnston, creative this theatre sports that again made teams, and there are teams today in Shanghai, in Nigeria, in Japan, in India, all over, so everywhere.

I just did a workshop, an online workshop, I was a student in it, that was based in Bangkok. Had students from all over Asia, and then also some European and American people involved. It’s just exploded.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s interesting. I mean, well, partly because I’m a Chicagoan. I think of improv, immediately, of course, I think of Second City. I don’t really think much beyond that. In fact, I think the subtitle of your book is beyond Second City. Yeah.

And what I’m learning just now, in speaking with you, is the extent to which there are, which makes sense when I hear you speak about different kinds of improvs. It’s not just sort of you stand up and start whatever comes into your different methods or different approaches. That’s interesting.

Amy Seham:

[crosstalk 00:27:14] emerged over time. I was saying the rhetoric about being equal and collaborating. Improvisation has this association with social justice, back to jazz and back to the ways in which oppressed people managed to be creative or have agency even within an oppressive situation.

I’m sure you encounter it when you’re doing the 30s, radicalism and so on, people used the notion of improvisation as equivalent to freedom, as equivalent to breaking out the prescription, the pre-scripted way that people are supposed to obey the script and the rules. And so it has that-

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, there’s a subversive or radical impulse to it. Yeah.

Amy Seham:

And that’s been important to people who’ve done it. But then, once it tries to become commercial, it [crosstalk 00:28:31] the shift.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, which is an old story. I mean, in so many areas. You’re also reminded me. I’m having a flashback here. Our now retired colleague, Professor Emeritus of theatre and dance, Robert Gardner, Rob Bob Gardner. He was doing a talk once about his teaching in Japan. Oh, it was a shop talk at Gustavus, and I think I was hosting it. He was talking about how he was teaching improv, and then he had us in the audience turn to the person to our right or left and try to do some improv. I always thought this would be fun. I’d be so good at it.

I found it incredibly difficult to do. I mean, surprisingly difficult. You’ve done it. I mean you’ve done so much. You’ve directed it, you’ve done it yourself. What is it about improv that draws you to it? Is it just the sense of freedom? What do you like about it? I was terrified, actually.

Amy Seham:

I mean, I now spent years kind of critiquing improv and yet I do love it. It’s a strange borderline to be walking because I do think there are ways that people have structured the way it’s taught and the way it’s performed that work to create a sense of freedom for white men. But with an insistence that that’s a universal quality. I’m both critiquing him and wanting to love it at the same time.

I mean, part of it is that if, and it goes back to my college days, or even to my childhood, if you’re not the person that the plays are already about, you can create your own. You might sit down and write it or you might develop it collaboratively with other people through improvisation, and in fact, a number of the early feminist theatres used improvisation as a technique for developing material.

Greg Kaster:

It’s interesting, the idea that you can create an identity, I guess, right? It’s in collaboration, right? I mean you’re not just-

Amy Seham:

That’s the trick. One of the things I’m finding is that if you have a like-minded group who share more or less the same values and background, then it’s fairly comfortable to just be creating and assuming that your troupe mates will support what you’re doing, recognize the references you’re making, join into the scene that you’re initiating and so on.

And in the interviews that I did in Chicago, it was very interesting and revealing, because one woman who worked at Second City who performed at Second City as well as other theatres there, she said, “Well, yeah. I mean, we all speak white male. We all know how to do that.” Because there’s a thing called group mind in improv that they champion and say, “This is where you get the flow experience. This is where you get the magic, is when the whole troupe is on the same page. And somehow magically, you all know what the next thing should be and how the story will end and how it’s going to happen. And it’s cosmic. It’s magic. It’s tapping into the universal story of man and so on.” But then here she says, “Well, yeah, okay, because we all speak white male, it actually isn’t universal.”

Greg Kaster:

It’s a universal white male.

Amy Seham:

Which is what we mostly learn to call the universal, right?

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Amy Seham:

I mean, that’s still pretty much our understanding of what universal is.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. When I think of social justice theatre, I think of serious stuff, heavy stuff, rightly or wrongly. And then when I think of improv, I think of comedy, again, rightly or wrongly. I mean, is that correct? I mean, are there social justice comedies that are also… I mean, is improv a part of drama as well?

Amy Seham:

Yeah. I would make a distinction between improv comedy performance and using improvisation to create a social justice piece or something like that. Part of what I encountered when I was doing the research, was people saying to me, “Well, you can’t have a political agenda going into improv because the pure form of improv is that you don’t plan ahead. You stay open to what’s going to happen between you and your partner. You don’t think, you just do, you are spontaneous. And that’s the only way that the magic happens.” And I said, “Well, feminist agenda, do you understand that no agenda is the mainstream power of people’s agenda? That there is no agenda.” Oh, no. And I got a huge pushback on that idea.

But most people doing improv have, for decades, said that it just incompatible with being political because you can’t control the message. And for the most part, you shouldn’t want to. But recently, I’m seeing much more improv that’s being deliberately political, and I’m fascinated. I’m trying to write a new book. It’s very hard because things keep happening that I should include. But there’s a group in Bangalore, India, and their whole focus is doing political improv.

Now, again, if they know that they’re all on the same page, they can improvise. It’s a question of what’s the makeup of your group, and are you having a pressure to consensus that’s not very legitimate? And that was a trend too that I found in my research, that people of color, women, gay and lesbian people would form their own improv troupes, because they would feel that they really couldn’t spontaneously create scenes that were about their own experience, because if they were in a mixed group the other improvisers just didn’t understand enough about what they were putting out. And so they’d end up just representing the gay person or the black person or the woman.

But if they’re in a group of all people with the same identity, then they all know they have enough in common that the consensus is in a different place, and they can create. And so those groups became more political.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s interesting, because if let’s say, they’re in a what we would say, a diverse group, then it may be harder for them to be as creative as they can be if they’re in an all black group, or all women’s groups. That’s interesting.

Amy Seham:

Especially because the material is coming out, is emergent, right?

Greg Kaster:

Yeah.

Amy Seham:

The material’s coming out spontaneously. There’s actually a lot of tension around it because there’s much, much, much more pressure to be politically correct now in improv, but how do you match that up with the notion that you’re supposed to be completely spontaneous? Well, you should not have any subconscious bias, but that’s pretty hard. I’ve said to people, “My feminism is still conscious. My instinctive reaction is to calm the angry man down however I have to do it.” Right?

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Amy Seham:

Or to whatever. But if I think, I try to have more self respect. And Keith Johnston, that I mentioned before, said, “You have to accept that ugly things are going to come out if you just completely freely improvise.” And that’s okay, but [crosstalk 00:38:52] it’s not okay today.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. I wonder about that. And I wonder about that. This is actually a perfect segue into your work with I Am, We Are at Gustavus. I mean, that’s the improv, right? I mean, it’s not-

Amy Seham:

The material gets developed that way. I have to say that group is no longer functioning, is no longer happening for the last four years now.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s sad. I wondered about that. You did such good work with them, and they did such good work. But how did that work? I mean, because they were dealing with some controversial subjects, in front of incoming students, as I mentioned in my intro, I mean, racism, sexism, hetero-sexism, et cetera. I mean talk a little bit about how that worked.

Amy Seham:

[inaudible 00:39:49], who was a guest professor at Gustavus before I got here, did a lot of that work with a group of students, and taught them about theatre of the oppressed, which is Augusto Boal’s social Justice theatre technique, where people create scenes to illustrate oppressive situations, and then invite audience members to participate in suggesting solutions. And then Boal really wanted audience members to get up and participate in the solution ideas. He has had a number of different approaches and techniques that he used for theatre of the oppressed. When I first came to Gustavus, and her guest stay was done, she had already left. But Denise Iverson Payne was still carrying it on out of the diversity center.

They still we’re using that kind of technique. But as the years went by, it became more and more about individuals writing things and bringing them in to the group to be improvised around or played with, but not primarily initiated through improvisation. And there were a number of reasons why that happened. One of which is the group started doing the… Oh, what’s that March thing? I forget the-

Greg Kaster:

Not the [inaudible 00:41:50]? Not that?

Amy Seham:

The conference.

Greg Kaster:

Oh, the building bridges conference.

Amy Seham:

I couldn’t remember building bridges for-

Greg Kaster:

Right. Yeah, the social justice conference that the students do each time.

Amy Seham:

So I Am, We Are became a really key element of that conference. I mean, I’m very proud of how many of the speakers would say, “The troupe did that. That is what you should be doing. Or that is what explains exactly the point I’m trying to make.” And so we always got a lot of excellent feedback from-

Greg Kaster:

Oh, yeah.

Amy Seham:

[crosstalk 00:42:28]. But to do a show about environmental racism, isn’t something you just improvise from your own experience.

Greg Kaster:

Sure.

Amy Seham:

Right? So you have to do-

Greg Kaster:

That makes sense.

Amy Seham:

… research and write something. And also, I don’t know, it was easier for people to write something and bring it in and move things along faster. I should write a book about this too someday. But the generations of students in the over 20 years who participated in that group and the things that shifted and changed over time, and the last few years where students were increasingly unwilling to represent, to be seen as there to represent their identity.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, okay. That’s interesting. Yeah. Yeah. That helps to explain what’s happened. You should do a book. I’m just thinking about how as the context has changed, then some of this is around, I suppose, PC, maybe, but some of it too is around this idea that identity is fluid, I don’t want to be… So many of my students, young people, seem to feel that, I don’t want to be this or [crosstalk 00:44:07] as this.

Amy Seham:

I don’t want to be a token in your [crosstalk 00:44:12] thing.

Greg Kaster:

Right. Right. Yeah. Well, so you’ve directed so much at Gustavus, I mean, my God and all kinds of different plays. I mean, I just love thinking about behind the scenes. I’m curious to hear you talk a little bit about the actual work of directing. I mean, you can pick an actual play you’ve worked on, if you like, but also just in general, what does directing involve?

Amy Seham:

Oh, okay. Well, you are collaborating with different groups of artists and trying to create a unified vision for what the production is going to be, while still respecting the artistry of the various artists that you’re working with.

I come in usually with a reason that I’ve chosen this play, and something that I’m interested in seeing through the play, and sometimes I have a visual image or something I want to do physically with it. And then I meet with the designers, and explain those things to them. And then each designer goes off and creates a design, which I then have to interact with. Both respect their work, but also kind of say, “Well, actually, that’s not really saying what I wanted to say.” Or, “She looks terrible in that.” Or something. And then you’re working with the actors, and it’s quite different to be working with student actors.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I wondered about that. Yeah.

Amy Seham:

And Gustavus undergraduates. There’s no graduate students to play older roles, for example, so that makes a difference. And Gustavus students are very over committed, so that makes a difference, because you really can’t expect the level of time or the level of commitment sometimes that you might otherwise want to do.

Greg Kaster:

I mean, how much rehearsing goes on for typical play at Gustavus? Let’s say you’re doing a… Pick a play, I don’t know, you’re doing [crosstalk 00:46:54]. Yeah.

Amy Seham:

It depends to some extent, but I would say something like eight or nine weeks of four nights a week.

Greg Kaster:

Wow.

Amy Seham:

And then an intense tech weekend and tech week. The tech weekend is all day Saturday, and all day Sunday, and then your dress rehearsals. And then after all that, you do three performances.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. That’s amazing. I mean, that’s an incredible time commitment on your part, and as you say, the student course.

Amy Seham:

Yeah. But don’t do theatre if you don’t enjoy rehearsing. I mean, if it’s only about the final product, then that’s a very small percentage.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, which is an important message for undergraduates, not just Gustavus undergraduates to hear. I mean it’s the same in any endeavor, right? I mean talking in some of my classes about writing, “Okay, here is a history book. This is the final product and you love it. But think about all the work that has gone into this or even just one article.” I mean, yeah, I think that’s an important message.

Sometimes I think young people, I shouldn’t general, but some people don’t have that kind of, as someone I know would say, a stick to it-ness. I mean, they want to get to the final product, the fun part, without necessarily all the sweat and tears on the way. And the fun too [inaudible 00:48:25], it’s not just sweat and tears, mixed with fun.

I mean you’ve done musicals, you’ve done drama, you’ve done comedies, you’ve done everything I can think of. Do you have a favorite genre you like to work with, or a favorite playwright or a favorite play to direct?

Amy Seham:

Yeah, I mean, I have a couple in different ways. One of my favorite playwrights is Caryl Churchill and I’ve [crosstalk 00:48:54] number of her plays. She’s a British playwright who uses sort of somewhat Brechtian technique where there’s realistic scenes, but then there’s also fantasy things. She did a play called Cloud Nine. The first act is in colonial Africa. And there’s a family. The wife is played by a male actor and the husband is played… She has people cross gender playing parts to heighten the performative quality of gender.

Greg Kaster:

Oh, gender. Yeah, that’s cool.

Amy Seham:

And then in the second act, you’re in modern day, and the same actors are now playing different roles. It’s still the family, and they’re 20 years older, even though 100 years have gone by. So anyway, it’s a very funny, effective play. Her other plays are great. My first play here at Gustavus I did Mad Forest by Caryl Churchill, which is about the Romanian revolution kind of… It takes place during [crosstalk 00:50:13] Romania.

I’m a director in an educational context, and I do think that having young people going through the process of understanding the text and bodying the characters, going through the process of living it, learn so much about the issue in ways that just reading the book or hearing their lecture is not going to do. That’s what I look at, but I also want it to be entertaining. I don’t think it should be dire. Social justice theatre, it shouldn’t make you think, “Oh, God, I’m going to be [crosstalk 00:51:09].”

Greg Kaster:

Right. That was what I was getting out earlier. When I hear the phrase, that’s sort of what I think of, “Oh my God, we’re going to need a drink after this.” Or whatever. It doesn’t have to be that way, as you’re saying, it could be very funny.

Amy Seham:

Exactly.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, and should be. And entertaining. This is also what you’re a just saying about your director in an educational context. That’s exactly right. I think that’s incredibly important to think about. You obviously do think about that. That’s a perfect segue to my next question, which is, what’s the case for theatre at a small liberal arts college?

I have to say, I mean, I don’t know how many plays I’ve gone to, not as many as you, obviously. But from day one at Gustavus, I have just been blown away by the talent of our students on stage, whether it’s in choir or whatever. I used to joke we should be the Juilliard of the Midwest or something. [inaudible 00:52:10] else.

What is it about theatre in the context of liberal arts that you think is important? Why be a theatre major at Gustavus? What’s your pitch?

Amy Seham:

There’s a couple of different ways to come at that. I mean, a lot of times we have students who want to major in theatre, and then they say, “Well, but my parents want me to have a practical major.” And I’ll say, “Look, pursuing a theatre career would be fine and great. You might not think that you’re going to be a professional actor, but the work you do in the theatre prepares you for anything. You have to work collaboratively with others. You have to articulate ideas. You have to work to deadline. You have to analyze text.” I mean, there’s every skill that anybody looking for somebody in a corporate setting, if that’s where you end up, or any setting, would value.

And our students, a lot of times they go into activism or social services, become ministers. People who are using the interactive skills, the people’s skills, the expressive and creative skills that we need to forge our way [crosstalk 00:53:50], right? Things are changing so fast, I could say I’m trained in something, or I could say I’m trained in being trainable, I’m trained-

Greg Kaster:

Exactly.

Amy Seham:

… in improvising and in finding a way to do it so that everyone can enjoy it.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I couldn’t agree more.

Amy Seham:

[crosstalk 00:54:13]. Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. As you’re speaking, I’m thinking too. I mean, one of the one of the things I definitely like about teaching is the performative aspects of it. I do love that. I mean some teachers are absolute hams, I like to think I’m not one, where it’s sort of, for me anyway, painful to watch, but it’s a performance I think. And I love that about it, and I’m now thinking maybe given what you just said, in fact, taking a theatre class might be required of everybody at a liberal arts college. Because you think about what we do out in the world, right? And so just our daily interactions in the workplace and beyond our performances of some sort.

Amy Seham:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I think it’s great. Man, we just have such a fabulous performing arts track record at Gustavus. The other thing I wanted to ask you, by the way, is the facility, say a little word about that at Gustavus, especially-

Amy Seham:

It’s exciting that we have this new space that’s just opened, the Gardiner Theatre.

Greg Kaster:

Made for Rob, right? Rob Gardiner.

Amy Seham:

Rob and Judy.

Greg Kaster:

Oh, both? Rob and Judy. Yeah.

Amy Seham:

Yeah. It’s a beautiful black box theatre, and what’s good about that is that it’s flexible. You can use it in any configuration by moving the chairs into different shapes and so forth. It’s perfect for experimental theatre and supports, devised theatre, but also it’s a great place to do something classical in a new way. I just really enjoy having audience feel part of a show. And I try to have different ways in which there’s an interaction between the show and the audience.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, you’re known for that. Again, in preparing for this conversation, there was a piece about you in the New York Times, way back when you were doing, I guess it was maybe Shakespeare in the Green in New Haven. The author of the article pointed that out, that meant a lot to you even then, that audience interaction.

Amy Seham:

[crosstalk 00:56:36] you have to engage the audience. And in order to engage the audience, you have to know what it is you are saying, and what you mean, and why you’re saying it. And you see Shakespeare where it’s pretty clear, even at the Guthrie, that the actors are doing their [inaudible 00:56:56] in their Shakespearean imagery, but they don’t really understand the nuances of what they’re saying. And that makes it really opaque for an audience, and the audience leaves and says, “Well, I guess I just don’t get Shakespeare.” And I have to say, “No, they’re not invested in what they’re saying.”

I love doing Shakespeare and I love doing Shakespeare in a way that will reach the current audience. And I just did Measure for Measure as a very major statement around the Me Too Movement because it centers around sexual harassment, sleep with me or your brother dies story.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Amy Seham:

In fact, some of my colleagues, my friends from graduate school, before I even announced I was doing Measure for Measure work, quoting that play in response to the Brett Kavanaugh hearings.

Greg Kaster:

That’s good.

Amy Seham:

There’s a line in it that says, “Who will believe thee Isabelle, my reputation is such that you will be dismissed. You won’t be believed.” It’s more eloquent than that.

Greg Kaster:

That’s great.

Amy Seham:

I was going to say when I was saying Caryl Churchill, that Shakespeare’s my other favorite way to go because he always gives.. The oppressed characters still have humanity and they still have eloquence. And you can turn the play to highlight different points of view that you want to highlight.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s true. One of my favorite courses as a… I can’t remember if it was an undergraduate or graduate course [inaudible 00:58:56] undergraduate, but it was a course on Shakespeare, for which I still have the book. I can remember the professor loved it, absolutely loved it.

The other thing we should mention here, by way of closing, is that even with the pandemic, even with COVID-19, you and your colleagues are still planning a season, whether that season will be in person or online or hybrid. Tell us a little bit about what’s on tap, what are you planning to produce this coming spring?

Amy Seham:

Coming up very soon, in a couple of weeks, is Henry McCarthy’s radio play that he did with a big group of students. And they turn their attention to learning that art form, which has a great history.

I’m very hopeful that I’ll be in person with the actors. When we did Mother Courage and we suddenly all had to go home, we kept trying to make Mother Courage but everyone was individually in their own home. So any kind of scene we tried to do on video or on Zoom, had to fake the notion that they were in the same room together at all. First I’m doing Rosencrantz and Guildenstern-

Greg Kaster:

Oh God, I love that. I love that play.

Amy Seham:

It’s very existentialist, and it’s very much about playing with the nature of reality and what is theatre, what is life, what is [crosstalk 01:00:44]?

Greg Kaster:

That Stoppard Tom, I love his stuff and I love that play.

Amy Seham:

So fascinating. What I’m hoping and planning is that we can be creative in how we videotape scenes, and then present it as an experimental video. And that the experimental quality can serve the uncertainty principle of the play of saying which things are real and which things are not. And then in the spring, I’m doing Three Sisters by Chekhov.

First of all, even hoping harder that we’re able to have the actors get together. But again, assuming that audiences still may not be comfortable to come to the theatre. So in that case, we’re going to try to create it like a staged film, filmed stage production, where we do multiple takes and we do editing, and we work with realistic acting in that sort of American way, that dovetailed right into film. Film and acting for the camera is certainly a skill that the students are excited about learning.

Greg Kaster:

As they say, in your business, the show must go on, now, in this case, it must go on maybe in new forms, but it’s got to go on. I mean, I just think the arts are so important. I mean, there are, of course, important at any time, but in a time like this when there seems to be so much darkness around us, the arts are so, so important. If I were in charge, we would be investing mightily in the arts, I’ll tell you that. But I’m not in charge.

I can’t let you go without asking about Hamilton, all right. Hype, great. What do you think about the casting? Have you seen it? I don’t know if you’ve seen it yet.

Amy Seham:

I saw the Chicago [crosstalk 01:03:03] Production.

Greg Kaster:

Okay, yeah. Yeah, I saw that.

Amy Seham:

Not yet watched the-

Greg Kaster:

The film version. Yeah.

Amy Seham:

Version.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah.

Amy Seham:

Which I’m looking forward to watching.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I did see that. What do you think? Thoughts about that?

Amy Seham:

I think it’s terrific. It’s the kind of thing that I love about a Caryl Churchill or about Shakespeare, where you’re being frankly theatrical, and using things that aren’t quite realistic to enliven a story that then needs to be told. If you just told the dry details of it, or told students to read an essay about Alexander Hamilton, they’re not getting the passion there, they’re not getting the vibrance of that we’re going to create a new country. I mean, it’s really hard to recapture what the zeitgeist was at a different historical moment, right?

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Amy Seham:

We’re always saying to the students like, they say, “Well, why don’t the girls just go to Moscow for God’s sake?” And they say, “Because in that time frame, you have to understand.”

Greg Kaster:

Context. Context, people. Context. Historical context.

Amy Seham:

I think that Hamilton is just a brilliant way of bringing something to audiences that is both true and not true at the same time, but is getting us closer to really understanding the excitement and passion of that moment than something that would have maybe tried to be very realistic.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s well said. I’m a huge fan. I’ve never seen it with Lin-Manuel except in the film, but love it. Absolutely love it. I’ve maybe in passing I mentioned to you I know our colleague Gary Hahn in classics loves it too. The three of us need to get together, either do a course or one day maybe produce this thing, you can direct.

Amy Seham:

Totally. Yeah. Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

That would be good. Well, this was so much fun. Thank you. Good luck with all the upcoming productions. People can find information on the Gustavus website, I know. And hopefully we’ll be back in the black box in Anderson Theatre before much longer. So take good care.

Amy Seham:

I enjoyed it.

Greg Kaster:

Break a leg.

Amy Seham:

Thank you. Thank you.

Greg Kaster:

All right. Thanks, Amy. Bye-bye.

Amy Seham:

Thank you. Bye-bye.