Professor Anna Versluis of the Gustavus geography department talks about how and why she became a geographer, researching, living in, and rethinking Haiti, southern Minnesota farmers’ attitudes toward changes in farming, the 2019 Gustavus Nobel Conference on climate change, the weekly Reconciliation Circles on campus, innovating her teaching, and the case for majoring in geography at Gustavus.

Season 5, Episode 8: From Scoffer to Geography Professor

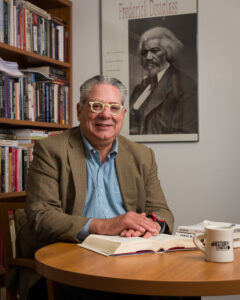

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus is produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of Gustavus Office of Marketing. Will Clark, senior communications studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast, and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

Maps and places on them, for some that’s what the word geography brings to mind, speak with my colleague, Anna Versluis about her work as a geographer however, and you quickly realize what an inadequate conception of her discipline that is. An expert in people’s interaction with the environment, especially around land use change, and also natural disasters. Anna earned her PhD in Geography at Clark University in Massachusetts and joined the Gustavus faculty in 2008. She recently completed a long stint as chair of the geography department and is affiliated with the environmental studies in Latin America, Latinx and Caribbean Studies programs at Gustavus.

Her courses include environmental geography, physical geography, environment and society, political ecology, remote sensing of the environment and a first term seminar titled, This Land. She’s an active in public scholar as well with numerous peer reviewed journal articles, academic conference presentations, invited lectures on various campuses and community talks. In 2015, 16, she was a Fulbright scholar in Haiti, where she had previously lived for three years and which she has visited often. Anna, also chaired last year’s Gustavus Nobel Conference on, “Climate Change: Facing Our Future.” And has been instrumental in creating a reconciliation circle on campus, which offers opportunities for conversation between Native American leader and members of the Gustavus community. Her work on nature society interactions is fascinating as well as incredibly timely and important, I would say more so each day, I’m delighted she could join me on the podcast. So welcome Anna, it’s great to have you.

Anna Versluis:

Thank you, Greg. It’s great to be here.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, thanks so much. One thing I love about this is we faculty, we tend to talk briefly on committees and so I get to talk to you at lengths finally, which is nice. Tell us a little bit about where you grew up and let’s see, you were a biology major if I’m remembering correctly, is that right? Let’s start there, where you grew up and how you came to attend Eastern Mennonite University and major in biology.

Anna Versluis:

I grew up in a number of different places, but for instance, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Yooper.

Greg Kaster:

Beautiful.

Anna Versluis:

Yep. I lived there for six years and then in Grand Rapids, Michigan. When I was speaking in Minnesota, I always have to remember to say, it’s Grand Rapids, Michigan not Grand Rapids, Minnesota. And then we moved to Western Pennsylvania and then I chose to go to college in Virginia at Anabaptist School, Eastern Mennonite University. So that was my path there, I grew up the oldest of five children, so a larger family, numerous dogs through the years. I had a happy childhood and there’s nothing in life like the gift of a happy childhood, I think.

Greg Kaster:

No kidding. Before we turned to your major in biology, did you grow up in an Anabaptist family and that’s your faith, tradition or how?

Anna Versluis:

My parents found the Anabaptist tradition when I was maybe eight years old, so they would say that they had been Mennonites for a while without knowing that term. So when they found the Mennonite Church, it cemented what the type of Christianity and the type of faith they had been practicing and studying. So, yes, I would say I grew up a Mennonite in Anabaptist.

Greg Kaster:

That’s neat. I mean, long, long history, fascinating history. And then so how did you wind up majoring in biology? Is that something you were already interested in high school?

Anna Versluis:

Gosh, I think I was one of those undergrads, I think we might have a few of them at Gustavus, who don’t know what to do and are maybe pretty good at math and science, and so pre-med seems like the only path.

Greg Kaster:

Right. We got a few, yeah.

Anna Versluis:

So I think when I started, I didn’t know what I wanted to do and I knew I could do pre-med and over the years as I took the courses, I decided I was really maybe more interested in the environmental aspects of biology more than pre-medicine. I remember I told my research methods and geography students just today, a story of… Actually, no, it was my FTs students, of a shadowed a physician and while I was a college student and that actually helped me decide not to become a physician. I didn’t think I would have patients to deal with, so many of the issues were coming from not exercising, smoking, drinking too much, having too much stress, not eating right. And I just didn’t think I would have the patience to deal with that day in and day out.

Greg Kaster:

It’s funny. It’s funny, I mean, a couple of things, one, yes, we have lots of students I suppose everywhere, but I love these stories about how my colleagues came to their major because rarely is… Sorry, came to their career, their discipline that they teach at Gustavus, because it’s rare that there’s a straight line. I found myself in history because of teachers but I was always testing much better in chemistry or something like that it was weird, I was supposed to be a chemist. Anyway, the other thing of course we know, you and I both know your experience is not that unusual, where students shadow and decide, “That’s exactly what I don’t want to do.” Whether it’s shadowing a lawyer or sometimes even a teacher doctor, et cetera, pretty common experience. So were you were moving into geography, do you think already as an undergraduate?

Anna Versluis:

As an undergraduate I had never heard of geography, several years out of college someone was talking and they mentioned someone who was a geography professor and I just scoffed at the idea that you could study geography past fourth grade or something. But I think I was, when I look back and see some of the courses I took as an undergraduate that were really influential to me, they really were geography classes although that wasn’t part of the name. So there was a class on food and population and it’s talking about, how do we feed the world, that sort of stuff, that interested me way back then and that’s geographical. But I have so many interests and so that’s always my problem, is figuring out what to do. And there was part of the allure of geography as it is such a broad discipline, that you can do so much.

Greg Kaster:

Yes. Well, I have to tell you, preparing for this chat with you and looking at all that you’ve done, one, that’s exactly what I felt that you’re incredibly… You’re interesting because you have so many interests and interdisciplinary and not only did I find that interesting, I find that very exciting. I mean, I think it’s so interesting when people… I have the same problem, what kind of history do I do? I don’t know, all of them, I love it all, I find they’re all interesting. I was trying to remember this… God it was famous at the time. When I was in graduate school there was a… I don’t know, I guess it’s probably still historical geography and we read a book that I was just blown away, by now of course I can’t, and I tried to find and remember it and I couldn’t today. But anyway, that shows up in your work, your varied interests. No, from there you want to get a master’s, is that right? Was it geography[inaudible 00:08:47]?

Anna Versluis:

I took some time away from being a student and so that’s when I first went to[crosstalk 00:08:55]. Yeah, I worked some odd jobs after college. I remember graduating from college and by that time, my family had moved to Oregon. So a friend and I set out on a road trip to Oregon and I just had no idea what I was going to do when I got there, but I thought I’ll just enjoy this road trip. After working some odd jobs and moving back home with my parents, moved to Haiti to work for Haitian human rights organization that’s now called RFL#, R-F-L and #, at that at the time I was working it was called, NCHR.

Greg Kaster:

And where was that in Haiti, was that Port-au-Prince?

Anna Versluis:

Yeah, Port-au-Prince.

Greg Kaster:

And so had you been abroad before, and if so, where?

Anna Versluis:

Yes. So one thing that interested me ever since I was a small child was to travel to other places in the world and I never had a chance until college. And so in college I was able to spend a semester of study away, partly in France and Belgium and partly in the Cote d’Ivoire in Western Africa. And then I had another opportunity to travel as a college student to Nepal in India, so I just enjoy those experiences so much.

Greg Kaster:

And you’ve written actually, I remember reading something you wrote about how important that is to learning, to mentor students. You’re really you’re really an advocate of that on the Gustavus Campus. And we’re lucky that we have such a strong track record of students studying abroad, I went to Mexico as a junior and just loved it with my then girlfriend, she was fluent in Spanish, which helped. You’re reinforcing my sense of you as adventurous at least by my standards because of where you chose to go, Nepal, part of Africa and then also Haiti. What do you remember? I mean, I remember vividly arriving in Mexico and just being in complete culture shock, even though I’d read about it and talked to my then girlfriend who had been there, I remember it vividly. What was it like to set foot in Haiti?

Anna Versluis:

I say, I’ll go anywhere there’s good food, and I haven’t yet been many places where there’s not good food. When you fly in Haiti, at least in 1998 when I first went there, the airplane lands on the tarmac and instead of having those [crosstalk 00:11:50]-

Greg Kaster:

Like, jet ways or something.

Anna Versluis:

Yes, there used to be no jet ways and so the door would open and it was just like, from the 1950s, you would walk down the stairs onto the tarmac. And for some reason I absolutely loved that experience. Sorry, it’s warm in Haiti and often humid so you can just… Yeah, that warmth and sunshine just immediately meets you. Yeah, it’s been so long but Haiti has so much to fill the senses, particularly Port-au-Prince, where there’s just sounds and smells and color and so much happening. As I was traveling from the airport to the guest house where I was going to stay at first, I was just trying to take it all in.

Greg Kaster:

You spoke French already?

Anna Versluis:

I had studied French and then when I got to Haiti, I studied Haitian, Haitian Creole.

Greg Kaster:

Okay, okay. I mean, three years, that seems like a long time to be anywhere that’s not home. Can you say a little bit more about what you were doing?

Anna Versluis:

Yeah. Three years as a 22 year old felt like a long commitment but three years does go quickly. In Haiti through an Anabaptist Organization called MCC, that’s a service organization that works in the United States and many different countries around the world. And so they had a history of working in Haiti and looking for Haitian organizations that might be helped by having a foreigner working for them. So I was technically a volunteer and was seconded to this human rights organization and the contract was for three years, So that’s what I did.

Greg Kaster:

This is going to require you to think back, although you’ve been back numerous times including for the Fulbright, but what do you know? I guess if one said Haiti to a group of people, random group of people, there are certainly images that would come to mind. I mean, extreme poverty, deforestation I suppose, earthquake for sure, because you were there right after that earthquake too, you are definitely adventurous. I mean, did you find to your understanding, the place changing radically or as a result of being there compared to what you thought about it beforehand?

Anna Versluis:

So sometimes people have asked me, “Well, why did you want to go live in Haiti?” And I said, “Well, I didn’t.” I heard only heard bad things about Haiti. When I heard Haiti, I thought violence, dust, deforestation, uprisings. I knew there was this person named Aristide, and I was always forgetting, was he the good guy or the bad guy? Before I went to Haiti, though this position came up and what interested me was not so much that it was in Haiti, but the position itself was a research position for the human rights organization. They were looking for someone who could do some research and writing and that’s what I thought I could do. I didn’t actually have much interest in Haiti nor human rights actually. Not that I’m not interested in human rights, but it wasn’t something I saw as like a career path, exactly.

I decided I need to learn something about Haiti, so I started reading and almost immediately I was just fascinated. It was really interesting and I had to completely rework my idea of what Haiti is, and why the words and images that I had gotten growing up about Haiti were incorrect or only a partial version.

Greg Kaster:

Go ahead, go ahead.

Anna Versluis:

Well and then through living in Haiti and having Haitian friends and colleagues, that even more than reading the books allowed me to revise my idea of what Haiti actually is.

Greg Kaster:

And what revisions took shape. I mean, even to this day, based on your other experiences there, if I say Haiti to you, what would you say?

Anna Versluis:

Well, for me, Haiti is a place where I have some very good friends and I just resonate with Haitians in a way that I sometimes have trouble with in my own country, I guess. There’s just so many good people who are level headed, intelligent and think well and have a sense of humor, I just want to be around them. I also think I’ve learned so much from Haiti, sometimes it’s out on a bit of a refiner’s fire type of learning that feels uncomfortable in the moment, but I do learn so much. It’s a country full of extraordinarily talented people and I find the culture to be… It’s not my culture but I just love being in that culture.

Greg Kaster:

I have to say I’m envious because I’ve always wanted to go there probably, since graduate school, when a friend and I, at the time we talked, we were both in graduate school, in history at Boston University, and we taught a course on American radicals. And one of the heroes for some of the radicals for the abolitionists was Toussaint, who we know is the hero of Haitian independence, which is the greatest slave revolt in the Western hemisphere. I know you know all this, but a lot of people don’t think about the debt that Haiti was saddled with by France, that has haunted it to this day. But I really would love to go there, now I know to have you come to my Atlantic slavery and freedom class by the way, because we do spend some time reading a little bit about it and talking about Haiti, the slave rebellion, the independence movement. Anyway, I’m envious, one day and not to mention the food… There must be one in the Twin Cities, maybe you know, is there a Haitian restaurant up here? I’ve looked, I haven’t found.

Anna Versluis:

I’ve not found one in the Twin Cities.

Greg Kaster:

Same here. No, same here. I was watching some of these food shows and they were featuring a Haitian, I don’t remember where it was. Maybe in Montreal, but a Haitian, a young Haitian, who had opened a chef, that’s not a myth, that sounds so good.

Anna Versluis:

And I would just say that, oftentimes in the United States, we study the French revolution, we study the American revolution and the Haitian revolution was just as spectacular, if not more so than those.

Greg Kaster:

Absolutely. Yeah, and it’s scared the what, out of our founding fathers or the slave holders, I mean, that’s exactly what so many slave holders feared. And some white and black abolitionists, well, a lot actually look to as an example. So I agree. Now, we should team teach this is another… Okay. Note to self, we can team teach a course on Haiti, a travel course, that would be fantastic. Have any of Gustavus students gone there to study? I’m not sure, I have no idea.

Anna Versluis:

Students have gone, usually through their church group but Gustavus unfortunately, won’t let us take students there, because it’s under… They look at the state department warning levels.

Greg Kaster:

All right, we’ll do it under the radar.

Anna Versluis:

I’ve been waiting for the levels to change for years now and I’m not real hopeful, but you never know.

Greg Kaster:

Well, all right it still a good idea, we have to do it. The other thing that I found so interesting, reading more about your work. You were there, I think it was during the Fulbright, that you were especially looking at and maybe earlier too but certainly during the Fulbright, looking at land use changes. And also if I understand it right, correct me if I’m wrong, but also looking at how in a certain, I guess it was a mountainous region of Haiti. How people there explained the natural disasters of flood and often deadly flash flooding versus how the media explains that. And that just got me thinking about how people who experience disasters, were you there? I don’t know, you weren’t there yet for the tornado in 1998, I guess?

Anna Versluis:

No.

Greg Kaster:

Thinking about that how that’s the only disaster I’ve ever experienced firsthand, but even then Kate and I were in New York when it happened, so we weren’t there at the actual day it happened. Anyway, just thinking about disaster narratives, I find that so interesting. So most long way to this question, which is just if you could say a little bit about the work you did there in 2015, 16 around land use changes and what you learned about how Haitians in that particular region explain, the flash flooding disasters versus how the media does.

Anna Versluis:

Yeah. So that was some earlier work and more with my dissertation. And I think what I learned there was, I had done a number of different studies in Haiti and people had been politely answering my questions, but then I fell upon just a very simple question for a semi-structured interview, is interviewing older people about how has land use changed in this rural mountainous watershed over your lifetime? And they would just sit back in their chair and say, “Well.” And it was as if they had just been waiting there all day for some researcher to come ask them that question and those stories were really fascinating. One of the things that’s interesting about it, is in the 40s there was a company called Shada, which was a society for Haitian American Development for agri… I can’t remember what it stands for in French nor English.

But they actually started timber cutting in this watershed and built a saw mill and so to this day if you go to the watershed, and up into the high areas where the native vegetation is this pine forest, it’s endemic to the Island. And you’ll find these little wood cabins, they totally look like something the U.S. Force Service would build. And in fact, they were built by people who also had worked for probably the U.S. Force Service, back in the United States. So the role that the United States has played and other foreign powers in land use in Haiti, it’s always there and influencing it in ways that are not always known outside of Haiti. So I was interested in hearing some of those stories.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s interesting. So I’m just thinking with Haiti, it sometimes seems to me… And again, I haven’t been there, I’ve read a little bit of Amy Will Lance and Paul Farmer, the doctor who’s there. But anyway, sort of blame the victim, I mean, what’s wrong with Haiti? they’re poor, they’re in poverty, their environment’s a disaster and yeah, we tend to… You’re right, I didn’t know anything about that until you just told us now. The other thing about your experience there, I wonder, it resonates with you, you said, but when you leave there or are you hopeful about Haiti? I’m just curious.

Anna Versluis:

Well, Haiti is a difficult place to live and it can be difficult for me to be there and certainly, what’s difficult is that it’s hard to get a good education. And if you succeed at that it’s so hard to get a job. The government does not serve the people in the way that it should. It’s always worked against the majority of the people and Haiti has… In order to secure loans from institutions like the World Bank and the IMF has had to agree to things that probably hurt the nation as well, to get those loans. So that has continued to play an unfortunate role in Haiti’s life. The vibrancy of people, culture, art, the vision for a local sustainable agriculture that I think we in the U.S. could learn so much more from, I don’t see those things going away anytime soon and that’s the heart of what Haiti is.

Greg Kaster:

I’d like to pick up right there because I know you’ve done… I mean, some of your work, I would, I guess you again correct me if I’m wrong, but it seems to be around what you just said, sustainable agriculture. And you did this project, a little film and also I think you presented it as a paper with a colleague Annika Erickson, who new in socio anthro. But anyway, talk a little bit about that I mean, you were working agriculture and land use and you gave a paper about… I think it was part of this project where you were interviewing farmers and I think what the papers called, the one I’m thinking was discourses on the farm and it’s contested goals and agriculture. Which I again, find fascinating but partly this is I will confess personal, I’m somehow the owner of a piece of a family farm, my mother grew up on a farm and we would stay Downstate Illinois, which is still in the family. And I’ve been interested in watching how that farm has changed, watching from afar how it’s changed.

I think my cousin is now putting wind turbines on the land, which some people don’t, anyway, I find that all interesting. So just talk a little bit about that work if you would.

Anna Versluis:

Yeah. I’m interested in land use and increasingly in agriculture, my husband’s a farmer. But Annika, and I… Yeah. Annika’s research was mostly been done in Mongolia and mine mostly in Haiti and here we find ourselves in St. Peter, Minnesota, and wanting to do research with students maybe not having the ability to travel to places like Mongolia and Haiti. Certainly, the students not usually having the language abilities to work there, so we thought, what could we do locally? And we came up with this idea that we could interview farmers in Nicollet County and surrounding counties about how farming has changed over their lifetime and what they see for farming going into the future. Because the changes have been, in the corn and bean agriculture that we have in Southern Minnesota, so great. So we’re interviewing people who can remember sometimes farming with horses.

They can remember when the tractors first came in and just in their lifetime, they’re seeing now, robotic tractors. Just the change and the speed of change, the size that farming has changed from going from, you could farm with 120 acres to now needing thousands of acres, a farmer with 2000 acres might now think that he or she is small, it’s just been wild. And having gone on that wild ride looking into the future, what do you see happening?

So this project was designed so students at Gustavus could do this research with us and so we randomly selected farmers who would agree to be interviewed by us and we’d drive to their farm and sit usually at their kitchen table and interview them, take a tour of their farm and really just have these very semi-structured interviews asking them about, how farming has changed and the challenges and what they like about farming?

Greg Kaster:

If you can generalize their feelings about the future and about farming or were they ready to call it quits or were they somewhat optimistic?

Anna Versluis:

A range of things but a lot of them felt like you couldn’t even say like, the changes in scale and technology have been so great it’s hard to even imagine or know what the future will bring. Some were pretty excited, like I remember one farmer saying she just loves all this new drone technology that’s being used to help with farming, that’s so exciting. A lot of them will say that they think they’re the last in their family, the last generation to farm. And so I think there’s a real sadness around that, so they might stay there.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I’ve even heard some of that, not in my own family.

Anna Versluis:

Yep. Yeah. And generally, a sense that farms are being forced to just get bigger, the equipment gets bigger, the number of acres gets bigger, the number of animals you have has to get higher. And really not seeing any other option than just continually needing to get bigger, which means you’re having to usually by someone else out, if we’re talking about land.

Greg Kaster:

Sure. Were any of the farmers engaged in… You know better than I what to call it, but organic farming or were they all doing traditional farming?

Anna Versluis:

They were all conventional farmers although some, for example one brother, sister pair, they will rent out space for 4-H kids to keep their animals there. So their farm yard looks like a traditional farm yard with goats and chickens and ducks and pigs and horses. So there were some people like that, but mostly it was corn and soybeans and dairy and hogs which represents, most of what agriculture is in Nicollet County and surrounding counties.

Greg Kaster:

Yes. I don’t think I knew your husband, so do you live on a farm or you live in town and then he goes out to do the farming, how does that work?

Anna Versluis:

We live in St. Peter and he farms in a couple of different counties. We don’t own land he rents, but he raises small grains, particularly wheat which he has milled into flour that you can buy at many places around Minnesota, but the St. Peter Co-op has it. It’s Ben Penner Farms, organic local flour, whole wheat and all purpose and the Turkey Red is the heritage wheat that he grows. When the Turkey Red grows, it can sometimes be so tall it’s over my head and when the wind blows it looks like what I imagine the native Prairie here would’ve looked like, just billowing like the sea.

Greg Kaster:

That is cool, wow. I think I’ve seen the flower, I’m not trying to… I’m pretty sure I have seen the flower part maybe in co-ops up in Minneapolis area, or maybe at the St. Peter Food Co-op too probably. That’s so interesting, I had no idea. I mean, you’re literally connected directly to what you’re researching obviously. I mean, these are related topics obviously but let’s move to, your work as the Chair of the Gustavus Nobel Conference last year. I think it was called, Climate Changed: Facing the Future, I thought it was a fantastic conference. It was both terrific and maybe terrifying at some point, I don’t know. But could you just a little bit about the conference in general, the Nobel Conference for listeners who don’t know much about it. And then that conference in particular, your work and helping to make it happen and your own thoughts about whether it was depressing, hopeful, a bit of both.

Anna Versluis:

Yeah. So the Nobel Conference is a major event that Gustavus puts on every year that looks at issues at the intersection of science and ethics. And so last year’s conference was climate change, this year’s was cancer. It was really an honor to get to chair the Climate Changed conference and meet the speakers to get to help choose them and meet them and learn from them. It was really good experience for me, I’m really grateful that Gustavus allowed me to do that. I learned so much and it was fascinating to get to listen to, and talk with all of these… Just a minute Eva, I’ll be with you, I’m doing an interview.

Eva:

Ma’am, can I watch “be the cat?”

Anna Versluis:

Yes. Excuse me.

Eva:

And the sheep?

Anna Versluis:

Either, wonder.

Greg Kaster:

That’s okay. So you were able to talk with really some, I mean, famous people in the field.

Anna Versluis:

Yes, yes. It was amazing to have some of these famous people, some of them who I count among my great heroes. At Gustavus and you’re eating meals with them, because that was back in the day where we could eat meals with people. Gosh I think their messages are so important and thinking that was a year ago and it feels so much longer it is [crosstalk 00:37:45]-

Greg Kaster:

It does.

Anna Versluis:

To think that as a nation, as a world, as a college, we just haven’t really made the progress we need to be making. We know we need to be doing a lot more and change how we’re living on this earth, so that the earth can continue to support us. So it’s a big question and a big problem, and it hasn’t gone away despite COVID, despite the election, despite the Black Lives Matter, which are all super important issues.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. Again, you may know more about this than I do, some argue that COVID or certainly the wildfires, the frequency of hurricanes. I mean, climate change is here, I was really dismayed maybe it was yesterday, I was listening to some senator’s question. May have been Senator Harris, Kamala Harris question Amy Coney Barrett, the Supreme Court Justice Nominee and her take on climate change seemed to be, “That’s debatable and so I don’t want to comment it’s not a factual matter.” And you want to say, “Really, you should have been at the Nobel Conference, because it’s not debatable, it’s here.” And I really thought that that message came through loudly and clearly at the conference. I found myself inspired by a lot of the speakers, the work that’s being done but also, depressed isn’t the right word, frustrated that there’s so much talent, so much knowledge, so much scientific ingenuity, entrepreneurial energy and then just up against politics.

The lack of a political will that is maddening, I just find that absolutely maddening given the… It’s not an exaggeration to say it’s an existential threat. I mean, there’s no question about that, there’s no debate.

Anna Versluis:

Right. It’s just like the pandemic public health officials had been saying for years that a pandemic could happen, will happen eventually and it does. And it’s just like the wildfires, we know these things will happen, it’s just a matter of when and who will get hurt most from them? But the climate has already changed and we’re now locked into it, continuing to change and so we’re going to have to find ways as best we can to live with it, and I don’t think that’s going to be easy or cheap and people will suffer and already are.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s right. I mean, you just said it weren’t cheap, there’s the economic dimension of it, the class race dimension of it. We’re seeing climate refugees in our own country of course, whether we want to acknowledge that or not. But it was an amazing conference, you did a fabulous job with it and this conference, this year’s was terrific as well. It was online, it was virtual but also fantastic, so yeah, I’m proud. One of the things I am so proud of about Gustavus is, the Nobel Conference and then the MAYDAY! Conference as well in the spring. The other thing I wanted to ask you about, because I honestly don’t know a whole lot about this and that’s your, your work around the reconciliation circle. I mean, I know it exists but could you say a little bit more about how that got started, the role you play and what it’s about?

Anna Versluis:

So, this is some of the most exciting work that I’m part of right now, is our bi-weekly reconciliation circles with, Francis Bettelyoun who is Lakota. And I’m not the one to tell the full story, it was actually the Director of the Nobel Conference, Lisa Heldke, who I believe first made the Gustavus connection with Francis as part of the Nobel Conference on soils two years ago. And so, Francis just been coming and having conversations with people like Gustavus, and so these reconciliation circles, the reconciliation is between the people whose homeland, we in st. Peter and Gustavus are occupying, the Dakota people and us people from various immigrant groups or people whose ancestors were slaves or however else we came to this country. And the whole, if I can say method, that Francis, is teaching me is fascinating to me, I could say that we do not use Robert’s Rules of Order.

We use a talking circle in which anyone is welcome and anyone can speak and there is no set agenda and everyone is listened to. So I think I’ve been learning so much from Francis, about pedagogy, about how to hold meetings and make decisions. It’s been a fascinating encounter, so anyone is welcome to come, we’re meeting online of course and it’s on the Gustavus calendar. So right now we’re meeting Thursdays at 3:30 every other week.

Greg Kaster:

Okay. I assume students have shown up or come fairly?

Anna Versluis:

Yep.

Greg Kaster:

That’s fantastic.

Anna Versluis:

It’s a mixture of staff and faculty, students and community members. And you just never quite know who will be there.

Greg Kaster:

Fascinating. As you’re speaking, I’m imagining, please ask Francis about leading a faculty meeting for us.

Anna Versluis:

It seems to me, I mean, maybe we’re talking to a small choir here, but the methods by which we conduct meetings are no longer working for us. And these meetings are really important and while they’re sometimes challenging, they should also be enjoyable.

Greg Kaster:

Yes. They don’t need to be painful, right?

Anna Versluis:

Exactly, yeah. So we need to talk about, be more creative about how we might work together and our visions together.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I’m definitely the choir here. Yeah, absolutely. You mentioned much earlier your… How many dogs did you say you have, three dogs or seven?

Anna Versluis:

Goodness, no. We have one dog with the energy of three.

Greg Kaster:

Kate and I love dogs also. My wife Kate, wouldn’t seen retired prof from the history department like this day but, she always wanted a St. Bernard, forget it, we couldn’t agree on that. She grew up with a German Shepherd, we had a Lab, a wonderful black Lab, both in St. Peter in Minneapolis named, Sam, she’d lived to be 16, is an awesome dog. And we used to do, mostly for fun to be honest with you, some training in Mankato, with a woman Maureen Rodriguez. And once we were all just having fun doing clicker training and I thought, we’ve got to bring this to the faculty. Maybe we’ve got to try clicker training, maybe that’s the answer, but I think Francis sounds more humane. Go ahead.

Anna Versluis:

Combining this with climate change and all of the environmental issues that we’re facing, Francis has really pushed me on how I’m living and really challenged me on that journey of, where am I trying to get to in terms of just how I live? So Francis and his partner are trying to raise all their own food and they’re really using almost nothing disposable. So if it can’t be composted or recycled… So I’ve been looking at all of this disposable stuff I use in my life, from a toothbrush to toilet paper to all sorts of things. We use tons of disposable things, plastic bags of course and we can’t continue doing that.

Greg Kaster:

Right. And the wasted food, I mean, I don’t know if this is true but I read something like, imagine going to the grocery store and you come out and let’s say, leave a bag or two in the parking lot, that’s what you might as well do, each of us we waste or maybe it’s each family, how much food we waste in this country it’s sort of mind-boggling. I’ve become more sensitive, I mean, I was sensitive I felt but much more so, now that my wife Kate, volunteers at a food shelf nearby where we live here in Minneapolis and also, we become part of a community garden growing produce for that shelf. So yeah, it takes some consciousness raising, I guess and really thinking about, as you said so, how are we living and where do we want to go? Where do we want to get?

I think those are good questions to always ask. You mentioned pedagogy a second ago, and that’s something I want to turn to now because, you’ve written about your interest in pedagogy and teaching geography, obviously that’s what you do. But also, how to teach things like information literacy let’s say, and the connections between geography and the liberal arts, I wonder if you could say a little bit about that? Then I’d like to ask about a couple of courses, but maybe just first, where your interest in pedagogy has taken you with respect to your teaching geography.

Anna Versluis:

Yeah. So one of the nice things about geography is I realized a few years ago, we don’t really have a cannon, we don’t have things we have to teach or a certain order that’s traditional to teach them and so it gives us a great deal of flexibility. And so I’ve been taking advantage of that. I’ve really enjoyed trying to teach classes where students get to help, design the class at times or have a say in what the class project will be or have a product that’s a real product. So one of the exciting times I did this was for the Nobel Conference, these conferences get planned, starting two years or more in advance. So two years before the Climate Change Conference, we had a class of students and it was that group of students working with faculty and staff that designed the conference and decided who the main speakers would be.

And we did it all through consensus, which was absolutely amazing when we finally achieved consensus after much contentious debate, leading up to that. So that was just a fantastic, some of these, I call them sometimes not classes, but almost like meetings because we’re working together on some common project. And unlike in many classes where you have students doing the same thing in more of a project atmosphere, it doesn’t make sense, that’s just redundant. So students are sometimes getting to choose, what interests them, how do they see their talents and interests fitting into this bigger project? And what are they going to propose that they do to move this forward? So I just have fun teaching some of my classes, creatively like that.

Greg Kaster:

That sounds fun, both for the students and for you. And I never thought about that of course, why would I am not a geographer, but the lack of a cannon and how that’s freeing and liberating. In history, we struggle with this coverage versus what I call it working out, we’re in a workshop, we’re going to work out with primary sources. Yeah, that sounds terrific and that is a great thing about a liberal arts college and Gustavus in particular where students have those opportunities. And it’s one of the things I definitely love about teaching at Gustavus which is the chance to experiment, teach outside of one’s bound disciplinary, boundaries even or at least disciplinary specialty, that sounds awesome. The other thing I wanted to ask you about two courses in particular. One, political ecology and just the word political there interests me already, what that’s about? And also your first term seminar, which you alluded to or mentioned a while back and I think, is it still called This Land? Is that the one you’re teaching?

Anna Versluis:

It is, yes.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, tell us a little bit about each of those courses, what they’re about.

Anna Versluis:

Political ecology is one of our geographic research capstone courses, so students are doing research in it, so it’s close to a thesis but maybe not quite. And we’ve only introduced to this in the last several years, so we’re still working out the details and figuring out what works and what doesn’t work. But the idea of political ecology, is responding to the fact that an awful lot of environmental science and studies is a political. And doesn’t recognize that you really can’t talk about environmental issues without being political, and by political meaning, there’s power relations inherent in the issues. So there’s winners and losers, there’s people who make the decisions and people who have to live with the decisions, that sort of thing is what we’re talking about in political ecology. So there’s a lot of geographers, as well as anthropologists, sociologists and others, who considered themselves political ecologists.

Annika Erickson would be another one, despite its name, it tends to be more social science than science. And that’s something that perhaps the field should work on better trying to integrate, those different areas of both the natural sciences and the social sciences.

Greg Kaster:

Sounds terrific in that point about power is incredibly important. This Land, which of course makes me want to sing, I won’t, since I have a probably singing voice, This Land Is Your Land. But what does that first term seminar about?

Anna Versluis:

Well, I’m looking for a better suggestions for the title.

Greg Kaster:

No, I like the title, I like it. I like it a lot.

Anna Versluis:

This time around, we’re actually working with Francis Bettelyoun, and it’s about the land that Gustavus that sits on and about Dakota Homeland Liberation. So we’ve read a book by the Dakota scholar [Viziatwi 00:53:28] who essentially puts forward a proposal for why the Dakota should get their land back and how this might happen. So that’s what we’re working with in that class and Francis then is… We have a small grant through, Thank You Kendall Center for engaged faculty learning, that’s allowing Francis, to work with the students and me as we learn and think about what small step we might take to help this dream come true.

Greg Kaster:

Boy, that sounds like a fantastic course as well, and perfect for the first term seminar where we’re supposed to be engaging students in questions of values and learning how to converse or speak, argue, that just sounds terrific. You’re an example I mean, all the faculty I interview we’re so lucky we have such creative colleagues, that there’s room to be creative in the first term seminar but in our other courses as well. I mean, every time I interview someone, a colleague from a different discipline, I end the podcast episode thinking I wish I had been majoring in that field. Geography is so much more interesting than you thought even, I’m glad to hear you say that earlier than you thought when you were much younger. Much more way beyond, “Here’s a map quiz folks.” Your working with [crosstalk 00:55:03] yeah, your work is so interesting. Let’s close by picking up on that by, hearing your so-called elevator pitch for the major. I mean, why come to a liberal arts college and major in geography?

Anna Versluis:

The first thing that comes to mind are my colleagues in the department, they’re fantastic, they’re excellent teachers and you’ll learn different things from each of us. I think we work really well as a team and our majors find a real sense of community and identity, while being challenged and supported in the department, it’s the people that makes it work. For the discipline itself, I think it’s fascinating, I do love maps and I love travel and I love the environment. So for me geography there’s two ways to define it, one is the spatial networks and flows and arrangements of things across the earth and the other is human environment interactions. So it’s the discipline that studies the relationship between humans and the world around us, including the built environment like cities.

And so that’s just fascinated me that relationship for my whole life. We teach a bunch of classes on stuff that matters to students so we have a race in space class, we have a political geography class, we have causes of climate change class, we have energy class. So just things that the world is facing, it’s opportunities for students to learn and discuss and contribute to these broader discussions. And what do our students go onto, there’s no job really that ever says, “Geographer.” And that’s okay, I tell students these disciplines are not mashed up to jobs in most cases, the important things are that you are learning how to problem solve, how to communicate, how to work as a team, how to manage time, how to write and think critically. And you’ll learn that in any discipline but what our majors tend to go on to do is they work in environmental sustainability. They work in urban and regional planning, they work in the geospatial sciences and they work in environmental law and they work in community and international development. So those are the main things that we see students going into.

Greg Kaster:

You sold me the part of it I can completely relate to and that I know I would love is, related to cities I live in. I appreciate the rural environment and I love cities, my dad grew up in Chicago. I love cities, I find land transformation in cities fascinating over time, even places like New York, I absolutely love that. Your majors are doing all kinds of interesting things. And what you said about the majors is exactly the same as history, history does not lead to X, It does not lead to a career. And then yes, you also said that’s true of so many disciplines in the liberal arts. Well, first of all people listening, young people, whether you’re a current Gustavus student or thinking of coming to take courses in geography with Professor Versluis, that is a highly recommended, I highly recommend that.

And so Anna, this has been a lot of fun, really a pleasure, I’m leaving as always stimulated and you make me want to go read a bunch of stuff about Haiti, and also go there. We can figure out how to get our students there some how.

Anna Versluis:

I would love that.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that would be fun. Take good care, stay safe and we’ll see you back on campus at some point.

Anna Versluis:

Thanks so much, Greg. It’s been great talking with you.

Greg Kaster:

Like wise.

Anna Versluis:

Thanks for the much patience.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, my pleasure. All right. Take care, Bye-bye.

Anna Versluis:

Bye-bye.