Professor Yurie Hong of the Gustavus classics department reflects on her love of classics (and the musical Hamilton), helping students see connections, the origins and nature of her award-winning community activism, and her activism’s relationship to her teaching.

Season 4, Episode 8: Making Connections as a Classicist and Activist

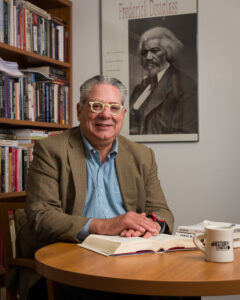

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus is produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of Gustavus Office of Marketing. Will Clark, senior communications studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast, and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

“There’s always a way to make a connection between things that seem really unrelated at first.” observes my colleague, Professor Yurie Hong of the Gustavus classics department. “The ability to make those connections is what enables people to adapt and to come up with creative and collaborative solutions. My goal is to help students make those connections between people, cultures and ideas. No matter what you do, your life and you work will be enriched if you can make those connections.”

As you will hear in this conversation, in addition to making connections in her teaching and scholarship, Yurie, more recently, has been making them as well across two spheres traditionally seen as quite separate and even incompatible, namely academia and activism. Academic Yurie received her PhD in Classics from the University of Washington, Seattle in 2007, and joined the Gustavus Classics Department that year where she teaches ancient Greek language, history and culture, as well as courses on sex, gender and reproduction in antiquity. She’s authored numerous scholarly publications, served as chair of her department, as well as the planning committee for the 2017 Gustavus Nobel conference on reproductive technologies, and participated in a National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute on facing death in ancient Greece.

Activist Yurie has, most notably, founded and led Indivisible St. Peter since January 2017, served on the board of Minnesota Indivisible Alliance since late 2018, and co-authored a successful Blandin Foundation grant for “supporting diversity and leadership initiatives in rural communities.” In April 2020, the YWCA at Mankato, Minnesota recognized the community impact of her social justice activism and leadership with a much-deserved Woman of Distinction Award. It’s no exaggeration to say that she is one of the most admired and respected members of the Gustavus faculty, and I am delighted to have this opportunity to speak with her about her work both on campus and in the broader community.

Welcome, Yurie. It’s great to have you on the podcast.

Yurie Hong:

Hi. Thanks, Greg. It’s really great to be here.

Greg Kaster:

Wonderful. I’m glad we could do this. Let’s start at the beginning. You’re really a historian, a classicist has to be a historian. Let’s start with your own history, if you would. Tell us a little bit about where you grew up and your path to classics.

Yurie Hong:

Yeah. Well, my parents moved to Los Angeles in the 70s from South Korea, and so my sisters and brother and I were all born in Los Angeles and grew up there and lived there for most of our lives. I was a pretty quiet kid. I didn’t have a ton of friends. My sisters were my friends. I read a lot, and I remember when I was young, my older sister had a mythology project that she had to do for school. I think she was in fifth grade, so that would’ve made me third grade, and I remember that she had to draw a picture of the underworld with all of the different myths, and she was explaining what she was drawing, and I was just fascinated. I loved the stories. I loved all the different gods. I thought it made a ton of sense that there was sort of chaotic, powerful beings, and that’s why life was so chaotic and uncertain and unfair.

I remember going to the library and wanting more and more stories, and I checked out all these books, and then after a while, I realized that there were different versions of the same stories. Some books said that Zeus had different wives, and some said that he had lots of girlfriends, and I remember thinking, “Well, which one is it because that makes a really big difference about how we’re supposed to view him.” Were these legitimate, sanctioned relationships and they were marriages, and that was just a thing that was okay? Was he not supposed to be running around on his wife, and he was having lots of girlfriends because that’s wrong. So what’s the deal, and why can’t they get their story straight?

So early on, I was interesting in these questions of what’s the original source say? Why are there different versions of things? What do these different versions mean? I was pretty nerdy about it. That kind of manifested in other areas of my life, as well, in terms of musical theater and things like that, but we can talk about that later. Yeah, I remember reading all these myths, and I became more familiar with ancient Greece and Rome, and by the time I got to college, the very first class I took at UCLA was a class on Greek history and civilization or culture, I should say. I found that I was raising my hand in class, which I never, ever, ever did.

I realized that there was something here, and I should probably stick with it, and I kept classes, classes and after a while, a couple years into school, my mom was like, “Well, what are you going to do with your life? What career do you want to pursue?” And I had really amazing teachers in high school. I thought well, teaching seems good, a worthwhile way to spend one’s life. So she said, “Well, if you’re going to teach, at least get a PhD and teach at the college level.” And I hadn’t ever really thought about that and I was like, “Well, okay.” What would I need to do to do that? I researched that a bit and realized that I would need to take languages and I figured, well, if I’m not good at this or I don’t like it, then I better find out fast.

So I enrolled in Greek, which had the reputation of being harder. I think it’s not actually harder, but because there’s a different alphabet, people get intimidated by it. So I enrolled in Intensive Greek over the summer and figured I would just jump right in and give myself a chance to switch if I didn’t like it or if it didn’t work out. I was okay at it, and I passed. I think I got a B, which was pretty good considering I had never taken an ancient language before, and I didn’t really know what I was doing or how to study properly. Then when I took Latin in the fall, the following fall, is when things all clicked, and then they started working together.

I’ve noticed that I was actually working a lot harder than I needed to, mostly because I wanted to be absolutely sure that I understood everything, and so there again, it was… Kind of to be honest, I’m a little bit lazy and self-indulgent, especially as a student. I would kind of get away with the least that I could do, and so with Classics, because I ended up doing more than I needed to do because I really, really, wanted to figure it out and learn it, I figured I should stick with that and give myself the best chance of being good at something.

Greg Kaster:

So you’re one of these people who knew, going into college, what you… I don’t know that you knew for sure you wanted to be a Classics major, but you went in already with a strong interest, and I love these stories, as I said many times in these podcasts and interviews because they highlight contingency. I mean, what if your sister hadn’t had that project. Right? You mentioned some of your high school teachers. Were you able to sort of nourish your interests in ancient mythology in high school? Or was that something you kind of had to do on your own?

Yurie Hong:

Yeah. It manifested in different ways, and so certainly in English. My English class was, I had a really great English teacher. Her name was [inaudible Efontas 00:07:55], she was a Mexican-American woman, and she had us read all kinds of things that were outside of the general list. So certainly, my knowledge of classics really helped because I understood a lot of these allusions or references, and when we read Tony Morrison, there’s a lot of classical references there.

So that certainly helped. I took this amazing AP Art History class, and so the mythological references and figures in art helped, as well. It was a useful framework for understanding because classics is so interdisciplinary. There’s history. There’s art. There’s literature. It kind of was a useful background for all these other works of art and cultural products that refer back to ancient Greece and Rome. So it was useful in that sense, but it did link Classics as part of larger love and interest for me in terms of how do people think? How do they organize themselves? How do they process their emotions and relationships? That’s something you can get from any culture and any cultural product. For me, it happened in the Classics.

I think for anyone, it can be anything else. There’s a lot of value to all of it.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. So often, I wish I had pursued my interest in, I guess I wouldn’t have known to call it Classics, but in the mythology. I had a great high school history teacher, really, but we read, who would it have been? Joseph Campbell, right?

Yurie Hong:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

I think we maybe read some of him, and then my dad’s said, you may remember, I’m Greek-American. So my father would occasionally drop names like Zeus, just something like, or Socrates into conversation. Anyway, and as you say, you’re already suggestion it, it’s just that it seems to encompass the good and the bad about life. Just every aspect of life is in the myths, which makes them so fascinating and fun. So you went to University of Washington, Seattle, and what was your area of… You were, obviously, pursuing a PhD in Classics, but with a particular focus?

Yurie Hong:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). Well, I actually started out… After I graduated from UCLA, I took a year off and I taught middle school, seventh and eighth grade Latin at Crossroads School in Santa Monica, which was really fascinating.

Greg Kaster:

I didn’t know you did that. That’s really interesting.

Yurie Hong:

Yeah! I loved it, and it forever shaped the way that I think about teaching, and I always knew that I was going to go to Grad School. I was just taking a year in between. I was studying abroad at the time I should have been applying, and I didn’t want to apply from abroad.

Greg Kaster:

Were you in Greece?

Yurie Hong:

No, I was in England, actually, for my junior year abroad, and so I took a little bit of time to save up a little bit of money and gain a little bit of teaching experience, and then also have the time to really research where I wanted to go to Grad school. So, yeah, University of Washington, Seattle. I really thought carefully about where I wanted to go, and the program there was very well balanced in terms of Greece and Rome, in terms of the different kinds of focuses, the different faculty it had, it was half male, half female. It was a pretty stable faculty, so that they weren’t, I wasn’t going to come for one person and then have that person leave.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Yurie Hong:

So I went in knowing that whatever I was interested in, I would probably change my mind based on other things that I would encounter because even though I had majored in Classics, I knew that it was a much broader field than I was going to be able to get an introduction to in undergrad. That’s why I wanted to keep all of my options open, and I think I probably went in thinking I was going to something on tragedy or something. I kind of did, but it got broader and more specific at the same time.

Greg Kaster:

Tell us a little bit about your dissertation, your PhD research, what it focused on.

Yurie Hong:

Yeah. It was interesting. When I started Grad School, I was like, “Well, I’m not going to do women just because I’m a woman,” and then eventually I made my way around to, “Well, just because I’m a woman doesn’t mean I can’t do women.” So I ended up doing my dissertation on representations of pregnancy and childbirth in Greek literature, and that topic got… I became interested in that topic, to be honest, because there was this ER episode that I saw in my first year in Grad School, and at the very end, this man and this woman come in and the woman’s in labor, and they’ve got a bunch of kids already, so no one’s nervous about it, and then one thing, maybe this cool couple that everyone like, but then one thing after another goes wrong, and then the episode ends with the father holding his newborn son, I think it was, then someone coming to say, “I’m really sorry your wife just died.”

I remember being like, “Oh my gosh! I never want to give birth, ever!” But also, that was burned on my brain, this kind of like, “Oh my god. What would that be like to be holding new life.” This is your newborn child and also to be grieving the loss of your life partner, and what would that be like? There’s really something primal and elemental about it, that there’s life and death. Even with modern medicine, there’s always the threat of death of the mother or the child, and the U.S. still has pretty unacceptably high maternal mortality rates and everything.

It doesn’t matter what time you’re living in, this is something to think about. I was interested in exploring that, and that topic allowed me to kind of be as interdisciplinary as possible. I didn’t want to nail myself down to one author or one genre. It was hard enough to nail down to Greece. I actually wanted to do Greece and Rome, but that’s too big. I focused a little bit on epic poetry. There’s a chapter on tragedy. There’s a chapter on medical texts. There’s a chapter on [heroditism 00:14:45] and historiography. This topic enabled me to play around in all of those different areas.

Greg Kaster:

I just love, again, the contingencies. So your sister, an episode of ER. It’s just great. That sounds like, maybe, a Greek tragedy or elements of it, that episode.

Yurie Hong:

Oh, [inaudible 00:15:08][crosstalk 00:15:08]

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. You’ve continued this research as you’ve gone on to motherhood, gender, reproduction, birth. Tell us a little bit about some of the… What did you find? What have you found as you’ve looked at representations of motherhood and reproduction in ancient Greek literature?

Yurie Hong:

Something that I was really reflecting on. I read a book chapter on motherhood in ancient Athens, kind of thinking about, envisioning, imagining, comparing the mothering experience, perhaps, for women of different classes and statuses, so elite Athenian women versus enslaved women versus working class Athenian women, and I was writing it while my two kids were very young, and I remember reflecting on the one hand, we have a presentist kind of bias where everything is so much better now, and everything in the past was terrible that the more I sat down to really thing about it, the more it became clear that, actually, being stuck in a house with just your nuclear family and small children that that’s harder, and trying to do your work at the same time is harder and a very different setup than in pre-industrialized societies where you would have a lot of people.

You’re in a community. A lot of people would be watching out for all of the kids. They’re running around, wreaking havoc, but also being with each other and being socialized, and have a greater range of freedom of movement, and these are all very large generalizations, but just it got me thinking about family structures and our household structures, I should say.

Greg Kaster:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Yurie Hong:

More clearly, and again, as I was saying before, that maternal mortality is maybe not quite as dangerous as it might have been for ancient Greek women where they didn’t have birth control and the more children you have, the more risks there are going forward, but at the same time, it doesn’t mean that there are zero risks for us today. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t areas that we can improve. So I think one of the things that I always think about with Classics and thinking about ancient people and cultures or people from just any different place or time or geographic location, even if it’s present day, is that there’s some things that are similar and some things that are different, and we have to keep both of those things in mind, maybe different proportions.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I couldn’t agree more. As you’re speaking, I’m thinking of, I think it’s David Lohenthal, who’s a historian geographer who wrote about the past as a foreign country. I think that’s the title of his classic book, but the ways we need to understand that the people of the past are, in some ways, like us and vice versa, but also different and try not to veer toward one pole or the other. I think that’s really hard, but I think that’s at the heart of history.

By the way, there’s some recent stuff that I haven’t read, that I just have read reviews, In early American history, in 19th century U.S. History about representations of motherhood, and I’m curious. So are you finding women are being glorified as mothers? Are there references to the dangers of motherhood, the loss of children in the literature you’ve looked at?

Yurie Hong:

Absolutely. There’s certainly, you look at tombstones, especially, there’s certain acknowledgment of the dangers of motherhood, and there’s a famous book or book chapter by Nicole Liverel called Mothers in Mourning, and it talks about women, well, mothers and their relationship to either death and dying in childbirth or in mourning the dead, dead children, dead husbands, and things like that, and that the very much, and we’re talking about Athenian citizen women, that very much the way for a woman to be honored or respected or gain status is through her relationships through her children, primarily, I would say, more than her husband. Husband too, but as the mother of Heracles, for example, or the mother of people who have done great things for a city, or the mother of heroes, that it’s their motherhood that causes them to be honored because that’s where they came from.

There’s also, you see there’s some challenges, too, later on when citizenship laws changed or become more specific, where then mothers become a weak link in the chains sometimes. There weren’t citizenship records or anything, but for men, they would be specifically enrolled and registered as a citizen and a son of their father who’s a citizen and all that. For women, there wasn’t quite that. So sometimes you see in the law cases that mothers become this point of where it’s like, “Oh, well, your mother wasn’t really a citizen, or wasn’t the daughter of a citizen, so therefore, you’re not really a citizen, and so you can’t bring this lawsuit against me.” They become a contested site for citizenship.

It’s a tricky thing, shall we say, but definitely motherhood is a route towards respectability, honor, in the same way today. We kind of have idealized ideas of motherhood and that gets people extra brownie points for being the best mom or…

Greg Kaster:

Right. How did the risks of childbirth and the death of children, how did those things manifest themselves in the literature you looked at?

Yurie Hong:

I think, mostly, what I was interested in was the use of this idea, the power and the vulnerability of birth or birthing as a metaphor for literary production, and it becomes really powerful as an actual concrete fact, but also in terms of the image, For example, Euripides’s Trojan women, and so thinking about what it means for a city to die and for people of that city to no longer be able to be born as Trojans, and so the Trojans are waiting to be… Troy has fallen, the men have been killed, and the Trojan women are waiting to be parceled out to their Greek captors. So, there’s a lot of reflecting on the causes of the war, the origins, the causes of trouble, in general, for Troy, and then there’s this really horrifying and powerful song in the middle where they envision that they’re going to go to their different spots in Greece, and they’re going to give birth to Greek sons, and that’s the final death of Troy.

This is also, we know that rape, it’s another way that war gets perpetrated on women’s bodies on purpose. It’s another form of genocide using reproduction, using birth as a tool or a weapon of genocide and death, so again, this birth and death thing. They become kind of like the Trojan horses, the Trojan horse comes in pregnant with armed men that destroy the city, and I could go on about this for a long time.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I love it. I never thought about the Trojan Horse as pregnant. Yes. That makes sense.

Yurie Hong:

[inaudible 00:23:47] says, “Pregnant with armed men.” That imagery is already there, and then what morphs into… So this meditation on the actual, material consequences of war for women, especially captive women, then morphs into the birth, instead, of the, we begin to witness the birth of oral epic or storytelling or mourning, lament about the Trojan War. So it’s this kind of circular thing where they’re giving birth to the lament songs about Troy that turn into the epics that then become glorious songs to commemorate that and to have immortal song as a replacement for the mortal bodies and the mortal city. Those are the kinds of things I was particularly interested in in that chapter with regard to the themes of birth and death and the dangers of that. I think it just becomes really powerful. The reality of it becomes a powerful symbol for other things.

Greg Kaster:

And as you suggested earlier, too, this is all about connections, the connections between what women are experiencing then as mothers, as birth givers, in death as well, and now. There are differences, as you also said, but there are connections and similarities. That goes back to the opening quote I read, which I love, and that leads me to ask you a bit about Gustavus. So you have a PhD in Classics from a major University program, and why Gustavus? I mean, was it simple that’s what the job market offered? Were you looking specifically to be at a liberal arts college? What brought you to Gustavus?

Yurie Hong:

I would say, yes. If the job market gives you a job, you take it. My husband and I were fortunate, actually, that we actually had a choice.

Greg Kaster:

Sean Easton, your husband. Yeah.

Yurie Hong:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

Hawthorne Classics.

Yurie Hong:

Also in department. We got the job offer at Gustavus, but then we also got a job offer at Arizona State University which was where we were at. I was there for a year, and he was there for two years, and it really wasn’t that hard of a choice. ASU, certainly offered a lot more money, but Gustavus offered everything else that we wanted, which was a community, an ethos that was more in line with how we felt about teaching, community research, and how you balance all of those things, the type of quality of life or family life we wanted to have, and ASU was just, it’s just opposite in every way. It wasn’t really so much of a choice.

It wasn’t a hard decision, I should say, and I have to admit, I was a little apprehensive about coming from Los Angeles and Seattle and then moving to St. Peter.

Greg Kaster:

Well, yeah. I wanted to ask you about that. Go ahead.

Yurie Hong:

I stepped into River Rock. [inaudible 00:27:07] took me to River Rock on my way out of town from my interview.

Greg Kaster:

Local coffee shop that we call love.

Yurie Hong:

Yes. River Rock Coffee, and I remember walking in, and it felt so much like a homey neighborhood, Seattle coffee shop that I was like, “Okay. I can do this. I’ll be fine if it’s got a place like this.” It’s worked out really well for us.

Greg Kaster:

I know Kate Wittenstein, you know Kate who recently retired from the history department, grew up in New York City, and I grew up in the burbs of Chicago, and those city people met in Boston. We came, like you and Sean, we were hired jointly at the time, which Gustavus had a pretty good track record of doing for couples. In any case, I remember thinking, “Oh my God. I don’t know.” From Boston to St. Peter, and there was no River Rock at that point, no movie theater, no nothing. It was, “Oh, can we do this?” Yeah, we could do it, and definitely the point about community, the community among the faculty, also crossing lines, faculty, staff, administrators, students, it’s really powerful.

Kate did go to a small liberal arts college. I did not. I went to big state school and then a big private university, Boston University, where we met. In any case, we’re glad that you and Sean came to our Gustavus. You’ve been teaching courses in Classics and also doing some interdisciplinary work with other faculty and other departments, but you’ve also become, especially in recent years, an activist. You’ve been quite involved in, what I would call, social justice activism, community-based activism, correct me, but tell us a little bit about that transition, if it is a transition. How have you found yourself moving into activism? My sense is you weren’t doing it early on at Gustavus. Go ahead.

Yurie Hong:

No. Yeah, no. I’m embarrassed to say that I was not involved.

Greg Kaster:

I didn’t meant that, by the way. [crosstalk 00:29:15]

Yurie Hong:

No, no. I like being up front about this because I think it’s important. It’s not a stable identity that some people are kind of born activists and some people stumble upon it and become inspired or moved or impelled to do it, and I think that, with a lot of things in life, you do things that you’re ready for. I think Gustavus and some of the relationships that I’ve been fortunate to have here has been actually 100% instrumental in my taking this path. I don’t know that I would’ve done this if I had been somewhere else, like in L.A., for example.

Basically, my second year at Gustavus, I had heard from other faculty members at about my level that, “Oh, you can sit in on people’s classes sometimes,” and things like that. Alisa Rosenthal from the Poli-Sci department, she’s no longer at Gustavus, but she was a huge influence and presence on campus when she was here, and she was in Poli-Sci and I had heard all these great things about her, and she was right in my building, and so I kind of drummed up the courage to be like, “Hey! Can I sit in on your Sex, Power and Politics class?” Because I’d actually never taken any women’s studies or any kinds of classes like that in college, and I just wanted to learn from her because I heard from students that she was so amazing. I was like, “What’s so amazing and how do I learn some of that?”

So she let me sit in on that class. It was, obviously, related to my own research interests and everything because it focused on a lot of things; forced sterilization, reproductive politics, and things like that, but in the modern era. I was there for many reasons. One of the things that she always emphasized for her class for students was that it’s not scary to go out and do things. They had to do some kind of project that was action-based and not just consciousness raising, and I remember this constant refrain of, “You don’t just have to think about stuff. You have to go do things.” Not that it doesn’t count, but it’s really important that you translate your thoughts into actions of some kind.

I remember really sitting there and being a student in that class and learning a ton, but also being really inspired to go out and do things, but I don’t think I really knew what that meant. I kind of sectioned that off and figured that was more for students to do. The same things I tell students to get involved or to go out and make their ideas count in the world, and that’s what I viewed my role as being, as being on the front end, the cheerleader or the coach for that, not a practitioner, myself. Because of that class, I submitted as a suggestion for the Nobel conference, the topic of reproductive technologies. Again, not because it had anything to do directly with my area of expertise because that’s all modern and forward-looking, but because it was something I was like, “Hey. This would be a cool thing to think about! [inaudible 00:32:23] and a lot of ethical stuff.”

And then a few years later, they’re like, “Oh, your topic has come up. So it’s your turn.” I was really daunted, but because there’s an infrastructure in place for planning, and I was only responsible for a portion of it, like the shaping of the topic and the running of the committee meetings to decide on speakers and that kind of thing, I was able to see firsthand. I was able to be part of the planning and coordinating, but didn’t have to do a lot of the really big-picture, logistical stuff, but I got to see how that all came together.

Greg Kaster:

It was a great conference, too. I remember it well. It was fantastic.

Yurie Hong:

It was so much fun, and to be part of the behind the scenes was really amazing and empowering to be like, “Oh.” The reason our conference took the shape that it did was because there were humanities people on that committee. For example, we had folks from biology, but we also had Maddalena Marinari in your department, in the history department was also there. There was a really good mix of people guiding that discussion about how do we construe this topic? It kind of came at this perfect time because 2017, by the 2016 election, we were a year into planning, but it wasn’t 2017.

Greg Kaster:

Right. Right. The election had not occurred.

Yurie Hong:

No, we were halfway through the planning, and so I already had a year’s worth of, “Oh this is how things go and how you plan a good project and how you get people on board to join the committee or how you keep people involved and interested even if they’re not going to commit to the committee but they’re interested in the topic, and then maybe later on they’ll do something else that’s connected to the conference so they’re more liable to if they’ve been kind of lurking in the background and hearing about how things are going, they’re more interested in… It’ll occur to them, I should say, to include stuff in their classes that would connect.

Those kinds of things were really helpful because then once the 2016 election happened, and I realized, just for myself that it’s not enough to just know about things and talk about them, for me anyway, and I do want to recognize all the contributions and life stages that people are at, but for me, I realized that I was sitting on a lot of skills that I had acquired through being a teacher and through being this head of the planning committee that I could also put to some kind of productive use. That’s when I started Indivisible St. Peter Greater Mankato. Indivisible Mankato merged with us a bit later on.

Really, I was envisioning at first, it was like maybe there’s be a collection of 50 people, me and some people that I knew and I would make handouts and emails and I could, well I know how to call meeting. I know how to send out meeting minutes. I know how to organize a Google Drive folder, and I’m pretty organized about that, and I know how to recognize when people are interested but busy, and I’ll get back to them, or people are really not interested and I’m not going to bother them anymore.

It hasn’t been that big of a shift. It’s different, certainly, but this is what we mean when we say transferable skills.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Yurie Hong:

Reading an article, summarizing it, posting it on Facebook, pulling relevant quotes, that’s not that different, in some ways, than my training as an academic. While I wish, on some level, that I had been involved sooner in my life, I also know that I spent my life thinking and learning and training, in some ways, that I didn’t know how I was going to use my skills, and then I had the skills and experiences and then I could just point them in this direction and it could take off.

Greg Kaster:

Oh, go ahead. Sorry.

Yurie Hong:

Than I did in my day job that I’ve been able to transfer rather efficiently over, I think.

Greg Kaster:

It fits so well with what you said a couple minutes ago, a phrase that I love, love so much I jotted it down, which is you do things that you are ready for. I also love, there’s this sense… I did my graduate training at Boston University where Howard Zin was there. One of my first experiences was the faculty, essential a general strike at Boston University, was the faculty, the clerical workers. It was amazing. Hence the president, the John Silver, as he was sometimes called the Shah of of Boston. In any case, there was Howard Zin. I didn’t have a class with him, but he was such a model of thinking, but also acting, and not seeing him as opposed, and in your case, I love the fact that it’s sitting in on a class taught by a colleague that inspires you, and that it’s your work on the Nobel Conference planning committee that helps you to realize the skills you have.

That is a form of activism, I would argue. Teaching, at least, can be a form of activism, as well. So I think, yeah, you were ready, and the time was right for you. You touch on this briefly, but let’s talk a little bit about how your work as an [academ-ission 00:38:28] and your work, maybe even identities as an activist, how they inform one another, and I don’t mean in some kind of crude way for listeners who are about to say, “Oh, see? Tenured radicals.” I don’t mean in some crude way that you go out and bring the clinical ideas into the classroom to force on students, but rather in other ways. How do the two inform each other? Do you think much about that?

Yurie Hong:

I do. I think about it a lot, and I also think about it in terms of narrative and in terms of how that narrative shifts depending on how you look at it. So I’m going to get a little bit personal here because I like these connections. One of the things I’ve really appreciated about classics is that it’s given me all these skills and all that, but I think what really pulled at me early on as a kid but also as a young adult, as a college student was that I could make these connections between these ancient Greeks and Romans with stuff that I was wrestling with in my personal life.

I remember reading Antigone, again it was like the first month of college, and there’s one part where one character, Haimon, is fighting with his dad, and he dad is being very strict and unyielding, and he says, “The tree that doesn’t bend in the storm will break and the sail that doesn’t loosen against the wind is going to tear.” I remember I put exclamation points in the margin saying “Yes!” Because my parents, who I love, are very, to my mind, very strict and unyielding, and so that was something I appreciated and thought how cool that there are these words some Greek guy wrote 2500 years ago and I find some resonance in them.

Classics has helped me process other things in my life, like the death of my brother, for example, but also understanding my grandmother and process how she fits into my story and vice versa. My grandmother came to the U.S. when my sister was born, and she had an arranged marriage when she was in South Korea and she and my grandfather were both in their teens, and in a lot of ways, there were a lot more parallels with her life and ancient Greek women’s lives than what I can actually fully comprehend and emotionally understand, and she did all of the things that you’re supposed to. She was quiet. She did all of the cooking and the cleaning and the watching kids, and even in our house, we loved her like crazy, but that’s what she was for us. We couldn’t have long extended conversations. We weren’t close in that way, but we were physically very emotionally very close to her, and I’ve always felt a little bit guilty, or not guilty, but her experience does not map onto what Americans value in terms of heroism or fighting against systems or being loud and having your voice heard and all of this kind of things.

What is that? Women who don’t break the rules, don’t make history, well behaved women.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Yurie Hong:

And she was a very well behaved woman! So how do we square that? Is that wrong? Is that right? And all of this. So I think about that a lot, and in class, I remember there were some students and they were very feminist, as I am very feminist as well, but there was a lot of condemnation of ancient Greek culture. They thought that’s so sexist and these women’s lives, they were treated as worthless and all they were were baby making machines and all this kind of thing. I was like, “How would you feel if an ancient Greek woman was in this room hearing you talk about her life this way?” They weren’t saying anything I disagree with, certainly, but at the same time, it was not respectful of the lives that lots of women live, and there’s reasons why people are invested in certain ways of living that, maybe, we don’t agree with.

The ability, even if you disagree with it and you can see the structures, like I am furious with the patriarchal systems or whatever that shaped my grandmother’s life that she didn’t have any choices, and both of those things can be true at the same time. In terms of activism, I think it’s really hard sometimes to see the humanity in others, and I think we do need to be careful and always center the humanity of people who have been dehumanized for generations or dehumanized in their current life. At the same time, for me, what’s important is trying to figure out why are people the way they are? How do we convince, or not convince, but how do we think through how we’re going to deal with anyone based on where they’re at, based on what is the humane, kind, generous, but also effective thing to do? There’s a practical element of it, as well.

I think activism is all about words, it’s about ideas, it’s about relationships, and maintaining some kind of humane connection to people such that the systems work better and in a more just way. That’s what, for me, being an academic has helped me think through a lot of that.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah because I think everything you just said about being an activist is also relevant to being a successful teacher, trying to figure out where the students are, trying to understand who they are, meeting them where they are, not necessarily staying there with them and having them stay where they are, but all of that is, as you said earlier, transferable to activism and vice versa.

What about at some other levels? Are there ways in activism you find yourself consciously or unconsciously drawing on your experiences as an activist in your teaching?

Yurie Hong:

In my teaching?

Greg Kaster:

Yes.

Yurie Hong:

Yeah. I think that in my teaching… I don’t talk about Indivisible and my activist work off-campus in the classroom. I will talk about American democracy and it’s various types of relationships to Athenian democracy. I will talk about the systems and the branches of government and why that’s important to know, and I will bring in contemporary events that will impact students’ lives and why they should know about it and encourage them to get involved, but I don’t do recruiting or active discussion of my work in that area in the classroom.

I do all the things that I mentioned already about helping students navigate differences of opinion or imagine a different life and maybe the constrainment of options explains why people live the lives that they do or struggle against society and societal structures that they do without changing the structures and help them see how those different stories change over time. Myth is actually perfect for that because myth, they’re like jewels that you hold up to the light and you turn it one way, and then it casts a different kind of spectrum of colors. You turn it another way, and you can’t see them at all.

That’s why you have so many different versions of Heracles or Hercules where he’s the bad guy, or he’s the buffoon, or he’s the hero. I think one of the most important things I can do in terms of in the classroom is helping students understand the stories that we tell and understand that myth and history or the news, these don’t function differently just because they’re different genres or types of information. They’re still narratives, and so the ability to understand the narrative as it changes and to interrogate your sources and who’s speaking at the time and all of that, and how that narrative changes if you adopt the perspective of a different character is really important, and that’s where my activism comes into the classroom, is the helping students question narratives and really think about what they want their role to be in the story they tell about their own lives.

Greg Kaster:

Music to my ears, I’m thinking, as a historian, and the way we talk about collective memory and narrative stories and what narrative, for example, of the U.S. Civil War is dominant at a particular time. How is that narrative being challenged? Yeah, I think, also this idea that that all happened in the past. It’s not really relevant to now. No! It’s incredibly relevant. Whether it’s the ancient world or history a hundred years ago, the legacies are all around us in both obvious ways and not so obvious. I think especially if people in this country say “Well, slavery, that ended more than a hundred years ago.” Well, yeah, but its legacies continue. Some of those legacies are complicated. It’s not just one terrible stories. Legacies of music and food, for example.

In any case, boy, I wish I had been a classics major. Maybe there’s still time. I can sit in on one of your classes.

Yurie Hong:

Always time.

Greg Kaster:

Switching gears here, one of the things that students know about you and I know about you is your love, which I share, your love of the musical of Alexander Hamilton. Could you tell us a little bit about what it is about that musical that grabs you?

Yurie Hong:

Yeah. Oh, there’s so many things. The music is awesome. The story’s awesome. It’s so layered, but I teach it in my myth class, in part because it’s great, and I think everyone should listen to it, but also because it’s so complex that it’s really useful for talking about origin stories and historical myth, and it complicates this idea that myth is what we had before we had history, and now we have history that’s based on facts, so myth is not something people believe anymore, and that’s actually not true.

A myth isn’t a lie. It’s not a bunch things that people believe that aren’t true. Myth is actually a compelling narrative that people recognize and that holds meaning for people whether they think that they’re true or not, kind of transcends that. So I love Hamilton because it’s very conscious about it’s own myth making, who lives, who dies, who tells your story. Eliza saying, “I’m taking myself out of the narrative. Now I’m putting myself back in the narrative.” It deals with sources because she burned the letters so now we don’t have them.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I couldn’t agree more. It’s incredible that way.

Yurie Hong:

It’s crying out for dissertations. It’s all been very intentionally and carefully put in there, and so I actually am not so interested in the way that ancient myths show up or are represented in modern works. I’m actually interested in connecting to seemingly unconnected dots, and so what I love about the Hamilton story is that it’s not about Classics, but it does still kind of track some of the hero narrative stuff. I

It also is very similar in some ways to the way that the ancient Romans thought about the founding of their city. In particular, they focus a lot on stories of the founding of Rome and what that meant and the war between two brothers and all that, at a moment when they, themselves were also in turmoil, where they were coming out of the long, protracted series of civil wars, and so when Augustus wins and he finally puts an end to all of this bloody infighting, then you have Virgil’s Linead looking back to Enias and how he came back from Troy to settle in Italy, and eventually the founder of Rome would be born, or Livie, who was the historian also writing at that time, saying, “I’m going to go back to the very beginnings from the founding of Rome and talk about our history all the way through.”

So when we’re in these moments of turmoil and change, we look to our beginnings to explain how we got her, but where that beginning starts, what it means, that often times changes depending on… It’s the story about the people who are telling the story more than it is about the actual origins, and what’s so useful about Hamilton is that it started when it was under the Obama administration, and nothing changed about the show, the words, the music, the performances. Nothing changed about that show from the Obama era to the Trump era, and yet the meaning of the show changed.

Greg Kaster:

Superb point, and it’s about historical context. The context has changed, as you’re saying, and also superb point, I think, an important insight about how in moments of crisis, we want to go back to origin stories, but we need to be thinking about the origins of those origin stories and how their meanings can change over time as context changes.

Yurie Hong:

And even from its performance on Broadway to now when it came out on Disney Plus, the meaning of the story changed again, so in the context about Mount Rushmore, and the context that the show, it celebrates America and its promise, and it feels different. There’s no native people in there, and so it now raises the uncomfortable thought that anything that celebrates America at all, it’s with recognizing the traumas perpetrated on indigenous peoples, and so it’s very complex in and of itself as a show, but it’s also complex in terms of the context outside the show and the way that we think about its role.

That’s what I love about it. It rewards thinking about it carefully.

Greg Kaster:

We need to do a course just on Hamilton at some point. We really do. I couldn’t agree more. I know we’ve both seen it multiple times, including the most recent iteration on Disney Plus.

I don’t want to end without asking you to say a little bit about classics at Gustavus. So imagine you’re speaking to a prospective student. Why classics at Gustavus? Why, at least, take a course or two, if not major in classics at Gustavus?

Yurie Hong:

I think that we, the Greek, Latin and Classics Studies Department at Gustavus has something for everyone because the field of Classics, by it’s nature, the way it’s been defined historically, interdisciplinary. If you have any interest in stories, in the past, in people who are similar or different from you, in languages and the ability to think critically in very nit-picky detailed ways, it can provide you with a window into all of these things, but it also, for good and bad, because Classics has been a privileged subject for centuries, there’s a value added of knowing that whatever you learn, it’s going to pop up again somewhere else, in your art history classes, in your English classes, in your history classes, in your philosophy classes.

There’s a built in strand of connect that if you recognize it, you can be able to take advantage of. Again, this is an argument against taking something that’s completely unrelated. There’s a lot of value in that, too, but I think that Classics does offer that, and I think that our faculty have lots of different diverse perspectives and ways of teaching and passion and interests that students can find classes, teachers, whatnot who will be able to encourage them, and I think that our department is especially interested in fostering students’ skills because it’s a small enough major that you can get a lot of attention, a lot of attention from your professors.

It’s really a great place to grow.

Greg Kaster:

And your majors go on to do all kinds of interesting things, contrary to what can you do with a history major, a classics major, an English major? Not true, right? They’re all over the place in successful careers and rewarding careers. I just love your quote about connections. You’ve come back to that a couple of times in our conversation. I think that’s so important. It really sums up what teaching and learning is really about. It’s definitely central to the work of historians, and I remember, it was some years ago, there was a big exhibit on Leonardo da Vinci, maybe it was in Chicago, might’ve been at the Museum of Science and Industry, but I remember one theme of that show was exactly what you’re talking about in that quote.

Da Vinci’s ability to make connections or see connections across seemingly disparate, unconnected things, and I think that’s so powerful, and I think that Classics, and I mean really any major at Gustavus nurtures that ability to make connections and see those, but you’re especially good at it.

There’s more I want to talk about, but we don’t have time. So we’ll have to continue this maybe another podcast. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk, and see you back on campus, I hope. Before long.

Yurie Hong:

This has been fun.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, it’s been great, Yurie. Thank you so much. Take care.

Yurie Hong:

You, too. Bye.

Greg Kaster:

Bye-bye.