In this inaugural episode, Pamela Connors, professor and chair of communication studies at Gustavus, and director of the Gustavus Deliberation and Dialogue Program, speaks about becoming a rhetorician, cultivating civic discourse in a polarized time, and directing a fascinating student-faculty research project on World War II refugees in Minnesota.

Season 1, Episode 1: Learning to Talk with One Another

Transcript:

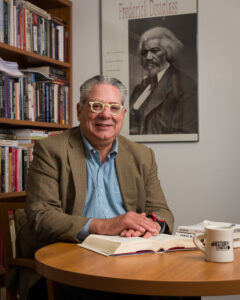

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus is produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of the Gustavus Office of Marketing; Will Clark, senior communication studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast; and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

My guest today is professor Pam Conners of communication studies or comm studies. And Pam, you’re the first for this new podcast, so congratulations on that.

Pam Conners:

Well, thank you.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. Excited to have you. You are also the chair of comm studies and the director of the Gustavus deliberation and dialogue program. So, it’s great to have you. The historian that I am, I like to start with a little bit of history about people. So, could you tell us a little bit about how you found your way to communication studies or comm studies, if that’s okay to call it that, and as that is your field of teaching and research?

Pam Conners:

Absolutely. Well, I found communication studies in college. My first year of undergraduate, I went to a small liberal arts college.

Greg Kaster:

That was Bates?

Pam Conners:

Bates College.

Greg Kaster:

Maine.

Pam Conners:

In Maine, yeah. And a little bit smaller than Gustavus. And I actually went to college and I thought I might be a math major. So, I got there, but I said, “I’m not sure if this is what I really want to do for the rest of my life.” But I love math, so I was studying it. But I was looking for something else that kind of captured my interest. And somebody recommended a class called contemporary rhetoric.

Greg Kaster:

Ah.

Pam Conners:

And I fell in love. And rhetoric, I’m a rhetorician, so we have sub-fields in communication studies. I study rhetoric, which is… Well, Aristotle would define it as the faculty of discovering in any situation all of the available means of persuasion.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Pam Conners:

We often hear about rhetoric in the world as being empty talk, but I argue that it is anything but, right?

Greg Kaster:

I agree.

Pam Conners:

In fact, rhetoric is examining how language and symbols are incredibly powerful, and how they shape the way we think, how we act, what we believe, how we communicate with each other.

Greg Kaster:

Was there a particular speech or address at that time that you remember that really stood out?

Pam Conners:

Absolutely. So, we looked at a bunch of different things in that class that really struck me. We looked at commercials on TV. We looked at news coverage, but we also studied Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech.

Greg Kaster:

Oh, yeah.

Pam Conners:

And everybody knows that that speech is phenomenal, right?

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Pam Conners:

Top speech of the 20th century. I mean, it’s really… It stands out. But what struck me was, we spent the whole class and as students in the class, we talked about that speech and all the things that we thought were really impressive and amazing in terms of how he crafted, organized it, how he used language to capture and captivate people’s attentions and imaginations about what was possible. And at the end of the class, we thought we had really unpacked that speech, and our professor, who was a rhetorician, spent 10 minutes just sort of summarizing all of the things that we hadn’t seen.

Greg Kaster:

You missed?

Pam Conners:

Right. And all of a sudden, I thought, we went from “this speech is great” to “this speech is unbelievably amazing.” And so, I was just captivated by how rich and deep and how powerful symbols and words could be in capturing our imaginations.

Greg Kaster:

It’s powerful. A lot of people don’t… I don’t know if you remember if you got into this, a lot of people don’t know that that march and that speech were also about economic opportunity.

Pam Conners:

Absolutely.

Greg Kaster:

It was called the March for… What’s it called? March on Washington for freedom and jobs.

Pam Conners:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

Or jobs and freedom.

Pam Conners:

Absolutely. And that sets some of my trajectory for my early work was really thinking about rhetoric of economics, so I actually took some of my math background, or my math interest, and combined it for thinking about, how do we use and how do language and discourse and public debates shape the way we think about…

Greg Kaster:

That’s interesting.

Pam Conners:

…different economies, but also people in different economic positions? Sometimes, we tend to overlook or describe people who don’t have a lot of resources and means in pretty negative ways. And we also then sort of uphold an image of, pull yourself up by your bootstraps and the American dream have a really powerful way of helping us think about, what does it mean to be a good American, which often means striving for great economic wealth and that sometimes can cause a lot of imbalances.

Greg Kaster:

Is that where your article on labor’s rhetoric came in?

Pam Conners:

Absolutely, yeah. So, I was interested a lot in discourses of work, and how those have shaped the way we think about what is good work, is worthwhile. But also, a lot of that shaped how we think about people who aren’t able to work, whether because of disability or because of poverty or because of right circumstance, and how those sort of unequal systems can sometimes get overlooked when we celebrate work as the only way, and certain types of work as being more valuable than others.

Greg Kaster:

Right, certain types of work. Yeah, that’s fascinating. I love that stuff. Labor historian here, so I love it.

Pam Conners:

Absolutely.

Greg Kaster:

I’m interested in this program, the Gustavus Deliberation and Dialogue Program, which I confess, as I said before we started recording, I had not known about. It sounds great. And I assume it has something to do with your overall interest in civic discourse, and you called it activism or citizen participation. Could you say a little bit about that program?

Pam Conners:

Sure.

Greg Kaster:

How it started and what it’s about.

Pam Conners:

Absolutely. Well, the communication studies department about three or four years ago started talking about, how could we use our expertise in communication studies to help guide students, and not just in our classes, but beyond the classroom to think about the role of civic discussion in public life? How do we talk with each other about our differences across those differences, and with those differences? So, how do we come together in conversation, and in disagreement sometimes, knowing that we all have different perspectives, but that we don’t need to give those up? We don’t need to give up our differences in order to work together, because we need to figure out how to work together.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Pam Conners:

And sometimes, particularly in a really politically divided, digitally dominated world, we can get really caught up in our enclaves and our differences. Right?

Greg Kaster:

Sure.

Pam Conners:

And sort of only say, “I’m only going to talk to people I agree with” or “I’m not sure how to talk with people that I don’t agree with.” So, what we developed, modeled after some other examples around the country is, how do we help cultivate and study and examine communication practices that help us become better at talking with each other?

Greg Kaster:

Has that made you more hopeful in the current climate, or…

Pam Conners:

It has.

Greg Kaster:

It has? Good.

Pam Conners:

And I think what we’ve seen is that students are really hungry for this too. So, what we do, we have a group of students who are what we call our fellows in our deliberation and dialogue program. And they learn strategies for researching and setting up conversations, and facilitating those conversations, so that people can feel comfortable coming together and saying, “Here’s what I believe. And this is what I think,” without being concerned about their perspective being demeaned or diminished.

Greg Kaster:

That’s great.

Pam Conners:

And when students enter the [dialogue]… We ask students what they think after they’ve participated and they inevitably say, “Wow, it was so refreshing to be able to say what I think and hear and learn from others.”

Greg Kaster:

Not be yelled at.

Pam Conners:

Right. And the goal isn’t at the end that you’ve changed your mind. Nobody has to change their mind.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Pam Conners:

But what we see are that people are saying, “But I learned something. I learned something more about the issue that I didn’t know. I learned something more about other students and other people that I didn’t know before I walked in. I have a better appreciation for who you are, because I learned to listen to you and you listened to me.”

Greg Kaster:

Is there, do you think there’s a… And here, I’m speaking as a historian and thinking about our tradition of very uncivil discourse in this country, duels in Congress. But is there a danger of this emphasis on civil discourse sort of muting debate that needs to happen, muting discussion of issues that really do need to happen, and about which some people are legitimately angry?

Pam Conners:

Yeah, absolutely. And often, what we talk about is civic discourse, right?

Greg Kaster:

Right. Okay.

Pam Conners:

So, it is important.

Greg Kaster:

That’s an important distinction.

Pam Conners:

In our communities, in order to be able to live together, is to learn how to talk with each other. That doesn’t mean that there aren’t moments and needs for really strong advocacy. And there are certainly many, many examples, historical examples of when sometimes incivility is the only thing that can disrupt communities that may be stuck in one way of thinking.

Greg Kaster:

So, incivility and… Or uncivil discourse and civic discourse are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Pam Conners:

Right. Exactly. And in our world, in our democracy, some calls for both.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Pam Conners:

But what we are seeing is that, when we think about, especially when I talk with students and not others, are disillusioned with kind of the national discourse that seems very polarized and very unwilling to kind of talk with each other, that thinking locally and thinking about our communities and the people in our communities that we have, we’re all humans. Right?

Greg Kaster:

Yes.

Pam Conners:

And that we have a humanity. I think we’re reminded of that when we sit down and talk with each other.

Greg Kaster:

That’s neat. I liked that, I liked the connection to the local too, which leads nicely to my next question, which has to do with this project called Bridging the Divide in Minnesota. Could you say a little bit about that? Which I think is really interesting.

Pam Conners:

Yeah. We’re-

Greg Kaster:

I assume it’s connected to the other.

Pam Conners:

Absolutely. We’re piloting that this year. So, Bridging the Divide started at the University of Chicago, at their Institute of Politics, and they were interested in how we could bring students from different areas and different perspectives from across sort of a rural-urban divide that we often see in the country. So, people coming from rural communities having a very different perspective that might guide their political identities than folks in urban areas.

Greg Kaster:

Called out state Minnesota, I think is the term?

Pam Conners:

Right. Right.

Greg Kaster:

It’s a rural. Yeah.

Pam Conners:

Yeah. And so, part of what they were looking for was, how do we build students’ ability to see themselves as civic leaders? What kinds of things can we do to bring those different perspectives together? So, the early versions that they’ve done and building in Chicago have been… We’re really productive and they wanted to expand that.

Greg Kaster:

That’s terrific.

Pam Conners:

So, they partnered with us in Minnesota and said, “Hey, what could you do? And could you build a, using your expertise in deliberation and dialogue, could you build a model that, what could we do if we really put students not just sort of hearing from experts, but really put them in conversation with each other and dialogue?”

Greg Kaster:

That’s terrific.

Pam Conners:

So, we had students from Gustavus and students from Minneapolis Community and Technical College. We had our first dialogue last week, actually, of a series of three we’re piloting this spring.

Greg Kaster:

And they all, the dialogues all take place within Minnesota? Or do you go to Chicago at some point?

Pam Conners:

This year, we’re going to be all in Minnesota. We went to Minneapolis College campus for the first one. We’re going to do one online in between. So, in March, we’ll follow up. And in the third one, the students will come to Gustavus on May Day.

Greg Kaster:

That’s great. Maybe we can bring Axelrod here.

Pam Conners:

That’s right.

Greg Kaster:

I like his podcast.

Pam Conners:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Thank you. That sounds so great. Then you’ve had this, I think just sounded terrific, this grant from the Council of Independent Colleges or the CIC called Humanities Research for the Public Good. If I’m remembering correctly, you’re still working on that a bit. And could you tell us a little bit about that project, its genesis, and where it’s at right now?

Pam Conners:

Absolutely. One of the things I love about this project is that it engages students really directly and explicitly in the research process in the humanities. And it also has been really interdisciplinary in nature, which highlights how we work together across this campus and not just in our own departments. So, this project is centered on looking at a box, an archival box of material in our Lutheran Church Archives here at Gustavus. That is from 1948 to 1952, papers from the Refugee Resettlement service.

Greg Kaster:

Oh, wow.

Pam Conners:

And it specifically looks at how there are pamphlets in there. There are documents that helped people get resettled in the area, specifically in this region.

Greg Kaster:

Oh, that’s terrific.

Pam Conners:

So, what’s really cool about it in terms of a local connection is that we can see the history right after World War II, of how here people in Saint Peter and then in the region, right around Nicollet County and beyond, really opened the doors to refugees, to host them in their homes, to help them get on their feet and find jobs.

Greg Kaster:

And would you know much about the backgrounds of these refugees? I mean, are some of them Jewish or not, or mostly—

Pam Conners:

Most of them are. They’re coming from Eastern Europe, a lot via, and Ukraine were two large places that they came from. Whether they… Not all of them were Jewish. I think some of them might’ve been, but many of them were just fleeing horrible circumstance in a devastated country, and Minnesota really set up and established an infrastructure for supporting and helping refugees.

Greg Kaster:

Wow.

Pam Conners:

And so, they came through. So, it’s been a really cool way of looking at our local history here in Saint Peter and the grant was part of what prompted this because they required you to use a collection from your own library. And it’s phenomenal that we have this.

Greg Kaster:

We have a great archive.

Pam Conners:

We have a wonderful archive here and as a… I’m not a historian per se, but I love to look at the rhetoric in particular historical moments. And so, I worked also, as I was putting this project together with Maddalena Marinari.

Greg Kaster:

Oh, right.

Pam Conners:

Who’s a history professor and an expert on immigration history, U.S. immigration history, to say, “Hey, can you help us sort of unpack some of this broader historical context, so that we could understand a little bit about and unpack some more of the local history?”

Greg Kaster:

That’s just great.

Pam Conners:

And we’re looking specifically, also at the language, and thinking about, how were refugees characterized, at the time?

Greg Kaster:

Are all the materials you’re looking at in English? From the refugee organizers or committee.

Pam Conners:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

Okay. So, you don’t have that language barrier.

Pam Conners:

We don’t have a language barrier with this one. Yeah, but we are, I mean, some of the pamphlets are amazing. So, we’re actually basing the theme of our… We’re doing a public exhibit that will be up at the Treaty Center, so.

Greg Kaster:

The Nicollet County Historical Society, right?

Pam Conners:

Yes, absolutely.

Greg Kaster:

Not far from campus. Come, everybody, and see it. When does it open? Do you know?

Pam Conners:

It will be open, we’re going to have an opening reception, I think it’s Wednesday, May 6, that will be open for the month of May in the Treaty Center.

Greg Kaster:

Terrific. Yeah.

Pam Conners:

For all who want to go through, but it’s going to be called Welcome New Neighbors: Refugee Resettlement in Minnesota from 1948 to 1952. But welcoming your neighbors comes from a pamphlet that was produced at the time to help people think about refugees as neighbors.

Greg Kaster:

That’s something.

Pam Conners:

A really important characterization. And other ways that refugees were framed was as an asset, how they can help support our communities. Thinking of people coming to our state as neighbors is a powerful rhetorical-

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Pam Conners:

To think about them as people who can help contribute our understandings of ourselves—

Greg Kaster:

That rhetoric is a little different from the rhetoric around immigration today. Some of that, right?

Pam Conners:

And those strains existed then too. Or in different ways.

Greg Kaster:

Sure. Sure. Well, that was my next question. Is it, I mean, is it mostly a happy story? Do you have any sense of where some of these refugees experiencing prejudice or discrimination for whatever reasons in the area, or was it all open arms as the pamphlet instructed?

Pam Conners:

It wasn’t all open arms. I think one of the things that we see though, is that the majority of people were about helping people settle into our community here. That doesn’t mean people didn’t face discrimination and didn’t face really challenging circumstances. It’s awful to uproot and have to leave your homeland, and resettle someplace that’s completely foreign and where you may or may not be well versed in the language. And we see that today-

Greg Kaster:

I was just going to say, today with-

Pam Conners:

And you’re not coming from great circumstance. You’re coming from near death, war-torn circumstance, so.

Greg Kaster:

In this area in particular, from parts of Africa, Somalia, Somalian refugees, yeah.

Pam Conners:

And that was part of what prompted this investigation, is that we’re thinking not just… We’re looking at our past around refugee resettlement so that we can also, as we move forward, think about it in relationship to our current opportunities to welcome our new neighbors.

Greg Kaster:

Exactly. I love how you’re doing all this work that involves students in research in the community as well. Let’s talk a little bit about comm studies, if I may. So, what are two reasons or so a student should at least take a course in comm studies if not major in it?

Pam Conners:

Oh, absolutely. So, I mean, communication studies. I often say probably about 99% of the conflicts that we have in the world have some sort of communication, miscommunication, or problem communicating at its core. We haven’t resolved and we have not perfected our communication. So, useful to think about how we can do that better. Our department has what we call a critical interpretive perspective on communication. So, we really study kind of three different areas. Rhetoric is one, how symbols and discourses shape our perspectives and identities. The second is media studies. So, we think about, how is communication mediated? Social media, television, etc. And really, those courses students often say they can never watch a TV show the same way again, because it really opens their eyes in terms of thinking about how influential and what kinds of different dynamics are at play. And then interpersonal and intercultural communication. So, how do we talk with each other on a regular basis?

Greg Kaster:

All very important.

Pam Conners:

Right? And those things are all, obviously, those areas are intertwined, but we think those courses and our courses, we really challenge students to be able to think critically, traditional liberal arts skills that you can get across this campus. But we really invested also in helping students be able to articulate their perspectives clearly. So, oral communication, how do you speak effectively and respond to others? That’s really what speaking is about-

Greg Kaster:

That’s important.

Pam Conners:

Responding to the circumstances in which you’re with. You have to read the situation and be able to respond before.

Greg Kaster:

In this day and age.

Pam Conners:

Or else you’re just talking at people.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, exactly.

Pam Conners:

And that’s not useful.

Greg Kaster:

Which there is a lot of. I don’t know if there’s more today than in the past, but I run into that all the time.

Pam Conners:

Yeah. So, we stress talking with, not talking at. And then of course, employers are really anxious to have strong communication as one of the number one things that they are looking for.

Greg Kaster:

Oral and written both. You’re right.

Pam Conners:

Yeah. To be able to write and to be able to speak. So, even if somebody doesn’t major in communication, you can get a lot from just a class, taking one course that can really open up your perspective.

Greg Kaster:

Right. And you’ve been teaching… So, you went to a liberal arts college, and you’re teaching at a liberal arts college for… You’ve been here since 2011 or something like that.

Pam Conners:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

What… Is there something special about Gustavus that you really enjoy, that either reminds you of your experience at Bates or is perhaps different from, or a bit of both?

Pam Conners:

What I love about Gustavus and liberal arts colleges generally, but I think is particularly true here, is how readily students come to embrace the opportunity to think critically about their own perspective. Again, that doesn’t mean change their mind and change who they are, but open up who they are to see the world through a lot of different lenses. And I think liberal arts identity of a college really embraces that, right?

Greg Kaster:

Agree.

Pam Conners:

To think about how who we are and how the sciences and how the social sciences and how humanities and the arts can really reframe our own sense of self and our sense of community.

Greg Kaster:

That’s right. Sense of self to our humanity.

Pam Conners:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Thank you so much. You’re doing great work. Very interesting. Now, I want to major in comm studies. Take care.

Pam Conners:

Thanks for having me, Greg.

Greg Kaster:

My pleasure. Thank you, Pam.